I'm reading The Blindness of Dr. Gray by Canon Sheehan, which was published in 1909. Canon Sheehan was an Irish priest-novelist, who died in 1913. His works were very successful in Ireland during his lifetime, and indeed afterwards. I remember my Catholic school's library had a whole series of his novels in gilt-edged, leather bound editions. Of course, I had no interest in him at that time. I simply noticed the name.

I've started several of his books but only finished one, which is The Triumph of Failure. He writes rather in the style of Charles Dickens, Sir Walter Scott or Anthony Trollope, and he has all the faults of this kind of author; occasional mawkishness, excessively broad humour, melodrama, redundant sub-plots, fixation on female chastity, etc. He's at his best when he writes about religion, but he seems determined to cram in a lot of other stuff, to prove how Homeric he is.

There is a sub-plot about gypsies and vagabonds in The Blindness of Dr. Gray which is incredibly dull; but whenever the story turns to Dr. Gray himself, a severe but dedicated parish priest, and his more broad-minded (but equally devout) curate, it holds my attention. The conversations between the two priests are absorbing, as are their private reflections.

In one particular scene, Dr. Gray takes his curate to task for his worldly occupations: playing the piano, and reading literature (Goethe and Jean Paul Richter) who Dr. Gray considers profane and useless. I was very moved by the subsequent description of Dr. Gray's views. I can even identify with them, even though I doubt this is what Canon Sheehan attended. I'm torn between an abiding attraction towards "culture" for its own sake and an intermittent conviction that human culture is trash, that only sacred studies are worth anything. Much as I love poetry, I'm dogged by the idea that all "literature" is decadent by its very nature. The excerpt is lengthy, but I'm going to transcribe it all:

When Dr. William Gray reached his home that afternoon, he was in one of those moods of agitated thoughts that were so frequent with him, and in which he had to walk up and down the room to regain composure. He was one of those serious and lofty thinkers that looked down upon literature and art as only fit for children dancing around the Maypole. He could not conceive how any priest could find an interest in such things, which he regarded as belonging so exclusively to a godless world that he regarded it as high treason for any of the captains of the Great Army to be attracted or drawn to them. He felt exactly towards the literary or accomplished priest, as a grim and wrinkled old field marshal would feel if he had heard that a young subaltern had stolen out of camp at midnight and gone over to the enemy's lines to listen to the strains of some Waldteufel waltz. He would accept no hint or suggestion of compromise with that mysterious "world", which, with all its wiles and magic, has been to the imagination of such ruthless logicians something like the vampire witches of medieval romance, from whose diabolic charms there was no escape but in instant flight. The meditation of the "Two Standards", and its terrific significance, was always before his eyes. Here was the Church, stretching back in apparently limitless cycles and illimitable, if variable power, to the very dawn of civilization. Here was the mighty fabric of theology, unshakable and unassailable, and founded on the metaphysic of the subtlest mind that had ever pondered over the vast abysses of human thought. Here were its churches, built not to music, but to the sound of prayer-- great poems and orisons that had welled out of the heart of Faith, and grown congealed in eternal forms. Here was its music, solemn, grave, majestic, as it fell from the viols of seraphs into the hearts of saints. Here was its mighty hierarchy of doctors and confessors-- pale, slight figures in dark robes, but more powerful and more aggressive than if they carried the knightly sword, or moved in the ranks of armoured conquerors. Here was its Art breathing of Heaven and the celestial forms that peopled the dreams of saints. Its literature was one poem and only one; but it lighted up Heaven, Earth and Hell.

And there in the opposite camp was the "world"-- that strange, mysterious, undefinable enemy, taking its Protean forms from climate, race and language. There were its theatres, coliseums, forums, opera-houses with all their pinchbeck and meretricious splendour, where all the vicious propensities of the human heart towards lust and cruelty were fanned and fostered by suggestive pictures or erotic verses or voluptuous music. There, too, were its philosophic systems, vaporous, fantastic, unreal as the smoke that wreathes itself above a witch's cauldron, or the ashes that lie entombed in the urns of dead gods. There again is its Art, fascinating, beautiful, but picturing only the dead commonplaces of a sordid existence, or the fatal and fated loveliness of a Lais or a Phryne. And there is its main prop and support-- this literature, aping a wisdom which it does not understand, or dealing with subjects that reveal the deformities and baseness, instead of the sacredness and nobility, of the race.

Saturday, September 30, 2017

Friday, September 29, 2017

Liberal Catholicism and Conversion

Recently, I've been developing a new conviction about liberal Catholicism. For a long time, I believed the liberal Catholic was simply naive and wrong-headed. I thought that he, or she, truly believed that a greater liberalization of the Catholic faith would reverse the fortunes of the Church in the West-- that new converts would flood into the Church, and that lapsed Catholics would return, the less emphasis there was on "thou shalt not" prescriptions and the more emphasis there was on the warm fuzzies.

What I wondered was: how? How could they think this? How could they think this, when the post-Vatican II era had witnessed such a spectacular exodus from the priesthood and religious orders, and such a dramatic decline in congregations? How could they think this, when the Church of England, which had implemented most of the reforms they wished for, has all but disappeared? Was it simply delusion, wilful blindness?

Increasingly, I've come to believe that many (most?) liberal Catholics do not expect that liberalizing the Church will reverse its decline. They don't particularly care about reversing the Church's decline. Perhaps they are even happy to see it decline.

A liberal Catholic is not a Catholic who is liberal, but a liberal who is Catholic, or who identifies with the Catholic "faith tradition". Their allegiance is not primarily to the Faith, but to liberalism. They are interested in using the resources and the moral weight of Catholicism to further the various liberal measures they support. What happens to Catholicism itself is of subsidiary importance.

This surely explains the attitude of so many religious orders, who seem blithely unconcerned with their imminent demise and their inability to attract new members. They are so intent upon their left-wing activism that it's simply not a priority for them. Their work will go on-- whether it is conducted by missionaries or NGOs is not important.

Behind all this I identify the "death of God" theology which sees the renunciation of Christianity itself as the ultimate act of Christian sacrifice. How far can Christians imitate the self-giving of Christ-- even beyond the sacrifice of their lives? Well, to sacrifice their very claim to be right, to sacrifice their claim to a revelation. Liberal Christianity is Christianity turned against itself, humble and contrite where it should be most proud and unapologetic. It agrees with Nietzsche: "To take upon oneself, not all punishment, but all guilt-- only that would be godlike."

What I wondered was: how? How could they think this? How could they think this, when the post-Vatican II era had witnessed such a spectacular exodus from the priesthood and religious orders, and such a dramatic decline in congregations? How could they think this, when the Church of England, which had implemented most of the reforms they wished for, has all but disappeared? Was it simply delusion, wilful blindness?

Increasingly, I've come to believe that many (most?) liberal Catholics do not expect that liberalizing the Church will reverse its decline. They don't particularly care about reversing the Church's decline. Perhaps they are even happy to see it decline.

A liberal Catholic is not a Catholic who is liberal, but a liberal who is Catholic, or who identifies with the Catholic "faith tradition". Their allegiance is not primarily to the Faith, but to liberalism. They are interested in using the resources and the moral weight of Catholicism to further the various liberal measures they support. What happens to Catholicism itself is of subsidiary importance.

This surely explains the attitude of so many religious orders, who seem blithely unconcerned with their imminent demise and their inability to attract new members. They are so intent upon their left-wing activism that it's simply not a priority for them. Their work will go on-- whether it is conducted by missionaries or NGOs is not important.

Behind all this I identify the "death of God" theology which sees the renunciation of Christianity itself as the ultimate act of Christian sacrifice. How far can Christians imitate the self-giving of Christ-- even beyond the sacrifice of their lives? Well, to sacrifice their very claim to be right, to sacrifice their claim to a revelation. Liberal Christianity is Christianity turned against itself, humble and contrite where it should be most proud and unapologetic. It agrees with Nietzsche: "To take upon oneself, not all punishment, but all guilt-- only that would be godlike."

Saturday, September 23, 2017

Rod Dreher on "Dialogue"

Thanks to Hibernicus of the Irish Catholics Forum for drawing my attention to this article from Rod Dreher on the liberal attitude towards "dialogue".

I feel mildly vindicated by this article. I've been sounding the alarm about political correctness for quite some time now. I really do believe its impossible to exaggerate just how insidious, how cancerous it is. And "dialogue" is the false flag under which political correctness loves to march. "Dialogue" sounds so harmless, so reasonable, so non-committal. But it ain't!

I feel mildly vindicated by this article. I've been sounding the alarm about political correctness for quite some time now. I really do believe its impossible to exaggerate just how insidious, how cancerous it is. And "dialogue" is the false flag under which political correctness loves to march. "Dialogue" sounds so harmless, so reasonable, so non-committal. But it ain't!

Writing and Faith

As I've mentioned before, I've been keeping a diary for more than two years. Every now and again, I spend some time browsing it. I was browsing it this evening and I came across this passage (actually something I posted on Facebook at the time):

I like how people look when they are walking outdoors. It's like there is a thicker outline around them. There is something more deliberate and cautious about them. This becomes even more pronounced if they are walking somewhere they have never been before. This occurred to me when someone asked me the direction on campus today. You can recognise when people are in a place that is unfamiliar and I think there is something very endearing about the sight.

This is probably why I like fish out of water films, like Crocodile Dundee, the best movie of the eighties (after The Breakfast Club, of course).

Reader, what do you think of that? I can't remember if many people reacted to it on Facebook, but I don't think they did.

Re-reading it, I find myself once again contemplating the act of faith required in writing-- faith in one's own ideas, their value.

When I think about the idea I've outlined above, I get terribly excited. It seems important to me. It suggests so much, although I can't say exactly why. Getting excited about such an idea is like finding yourself in a passage which may lead to a cavern, or finding a hidden panel that opens onto...who knows what?

I realize how strange this seems. Very, very often, for as long as I can remember, I've found myself getting very excited about some idea which I can barely articulate, and desperately wanting to convey that idea in some kind of written form.

At the same time, I'm a deeply insecure person, and I'm always dogged by the question: "Why should anyone else care about your strange enthusiasms? Perhaps you struggle to convey this idea because there is quite simply nothing to convey?"

I'm deeply envious of the writers who manage to take their inspirations and convey them to thousands, tens of thousands, millions of people. I imagine that it requires a tremendous amount of faith, of faith in the validity of their own thoughts. Because surely anything that's original, that's creative, started out as simply being odd. I once read an interview with Sue Townsend, writer of the Adrian Mole books, in which she recalled that, when she was younger, she often found herself pointing out things to other people which they found completely uninteresting-- they didn't know why she would be pointing them out in the first place. I found a lot of consolation in that!

I like how people look when they are walking outdoors. It's like there is a thicker outline around them. There is something more deliberate and cautious about them. This becomes even more pronounced if they are walking somewhere they have never been before. This occurred to me when someone asked me the direction on campus today. You can recognise when people are in a place that is unfamiliar and I think there is something very endearing about the sight.

This is probably why I like fish out of water films, like Crocodile Dundee, the best movie of the eighties (after The Breakfast Club, of course).

Reader, what do you think of that? I can't remember if many people reacted to it on Facebook, but I don't think they did.

Re-reading it, I find myself once again contemplating the act of faith required in writing-- faith in one's own ideas, their value.

When I think about the idea I've outlined above, I get terribly excited. It seems important to me. It suggests so much, although I can't say exactly why. Getting excited about such an idea is like finding yourself in a passage which may lead to a cavern, or finding a hidden panel that opens onto...who knows what?

I realize how strange this seems. Very, very often, for as long as I can remember, I've found myself getting very excited about some idea which I can barely articulate, and desperately wanting to convey that idea in some kind of written form.

At the same time, I'm a deeply insecure person, and I'm always dogged by the question: "Why should anyone else care about your strange enthusiasms? Perhaps you struggle to convey this idea because there is quite simply nothing to convey?"

I'm deeply envious of the writers who manage to take their inspirations and convey them to thousands, tens of thousands, millions of people. I imagine that it requires a tremendous amount of faith, of faith in the validity of their own thoughts. Because surely anything that's original, that's creative, started out as simply being odd. I once read an interview with Sue Townsend, writer of the Adrian Mole books, in which she recalled that, when she was younger, she often found herself pointing out things to other people which they found completely uninteresting-- they didn't know why she would be pointing them out in the first place. I found a lot of consolation in that!

Friday, September 22, 2017

Hurray for Culture Night

Tonight is the thirteenth Culture Night in Ireland. It's an institution which has gained momentum over the years (I certainly hadn't heard about it thirteen years ago) and has now reached the stage where people ask each other: "What are you doing for Culture Night?" As a lover of traditions, I approve of this.

On this one night of the year, cultural institutions give free admission or put on special events.

The Central Catholic Library is open for it and has a display about writers of the Irish Literary Revival.

I moan about modern Ireland enough, so I like to celebrate the good when I can.

Doubtless we will have a horror movie set on Culture Night if it becomes popular enough!

On this one night of the year, cultural institutions give free admission or put on special events.

The Central Catholic Library is open for it and has a display about writers of the Irish Literary Revival.

I moan about modern Ireland enough, so I like to celebrate the good when I can.

Doubtless we will have a horror movie set on Culture Night if it becomes popular enough!

Thursday, September 21, 2017

Time and Eternity

Red Rose, proud Rose, sad Rose of all my days!

Come near me, while I sing the ancient ways:

Cuchulain battling with the bitter tide;

The Druid, grey, wood-nurtured, quiet-eyed,

Who cast round Fergus dreams, and ruin untold;

And thine own sadness, whereof stars, grown old

In dancing silver-sandalled on the sea,

Sing in their high and lonely melody.

Come near, that no more blinded by man's fate,

I find under the boughs of love and hate,

In all poor foolish things that live a day,

Eternal beauty wandering on her way.

Come near, come near, come near—Ah, leave me still

A little space for the rose-breath to fill!

Lest I no more hear common things that crave;

The weak worm hiding down in its small cave,

The field-mouse running by me in the grass,

And heavy mortal hopes that toil and pass;

But seek alone to hear the strange things said

By God to the bright hearts of those long dead...

That's Yeats, of course, in "To the Rose upon the Rood of Time". The lines often come to my mind, because I'm very familiar with the conflict they describe. I've always been familiar with it. I've written about it on this blog before, especially in this post.

I suppose I could describe it as "love of the world, versus hatred of the world". Or love of eternity, as opposed to the love of time.

The mystical side of me, the side that is drawn towards romantic nationalism and poetry, craves all that is elevated and elemental; ritual, hierarchy, idealism, nature, solemnity, poetry, proverbs, mythology, high romance...

But then there is the other side of me, the lover of the ordinary; of news bulletins, diaries, the hum of voices on the air, pop songs playing in supermarkets, nerds of every description, Hallmark shops, newspaper cartoons, election posters, cinemas, all human life in all its delicious banality...

One side of me thrills to "The Passing of Arthur" by Tennyson ("clothed in white samite, mystic, wonderful"), while another part of me thrills to "Snow" by Louis Macneice ("the drunkenness of things being various").

Part of me is the highest of High Tories, while another part of me feels very home in liberal democracy. (By liberal I do not mean anti-life, anti-family, or anti-religion. I mean the messiness of liberal democracy.)

Part of me wishes to withdraw from all pop culture and current affairs, and part of me loves to gorge on three hour TV documentaries with titles like "The One Hundred Scariest Movie Moments".

I have been tossed between these two extremes all my life, and I'm really beginning to think that is my fate unto death.

Come near me, while I sing the ancient ways:

Cuchulain battling with the bitter tide;

The Druid, grey, wood-nurtured, quiet-eyed,

Who cast round Fergus dreams, and ruin untold;

And thine own sadness, whereof stars, grown old

In dancing silver-sandalled on the sea,

Sing in their high and lonely melody.

Come near, that no more blinded by man's fate,

I find under the boughs of love and hate,

In all poor foolish things that live a day,

Eternal beauty wandering on her way.

Come near, come near, come near—Ah, leave me still

A little space for the rose-breath to fill!

Lest I no more hear common things that crave;

The weak worm hiding down in its small cave,

The field-mouse running by me in the grass,

And heavy mortal hopes that toil and pass;

But seek alone to hear the strange things said

By God to the bright hearts of those long dead...

That's Yeats, of course, in "To the Rose upon the Rood of Time". The lines often come to my mind, because I'm very familiar with the conflict they describe. I've always been familiar with it. I've written about it on this blog before, especially in this post.

I suppose I could describe it as "love of the world, versus hatred of the world". Or love of eternity, as opposed to the love of time.

The mystical side of me, the side that is drawn towards romantic nationalism and poetry, craves all that is elevated and elemental; ritual, hierarchy, idealism, nature, solemnity, poetry, proverbs, mythology, high romance...

But then there is the other side of me, the lover of the ordinary; of news bulletins, diaries, the hum of voices on the air, pop songs playing in supermarkets, nerds of every description, Hallmark shops, newspaper cartoons, election posters, cinemas, all human life in all its delicious banality...

One side of me thrills to "The Passing of Arthur" by Tennyson ("clothed in white samite, mystic, wonderful"), while another part of me thrills to "Snow" by Louis Macneice ("the drunkenness of things being various").

Part of me is the highest of High Tories, while another part of me feels very home in liberal democracy. (By liberal I do not mean anti-life, anti-family, or anti-religion. I mean the messiness of liberal democracy.)

Part of me wishes to withdraw from all pop culture and current affairs, and part of me loves to gorge on three hour TV documentaries with titles like "The One Hundred Scariest Movie Moments".

I have been tossed between these two extremes all my life, and I'm really beginning to think that is my fate unto death.

The Heelers Diaries

There is an Irish blog called The Heelers Diaries which has been regularly updated since 2005. This is sterling dedication to the cause of the Catholic faith and to poetry (which are the two main themes of the blog).

The blog's slogan is: "The fantasy world of Ireland's greatest living poet". I thought that was me!

There is no blog quite like it and I'm ashamed I haven't plugged it yet.

The blog's slogan is: "The fantasy world of Ireland's greatest living poet". I thought that was me!

There is no blog quite like it and I'm ashamed I haven't plugged it yet.

Irish Traditions and Customs

Regular readers will remember me mentioning, fadó fadó (a long, long time ago), an ambition to compile a comprehensive list of Irish traditions and customs, including the sort that generally fly under the radar.

Well, I'm still a long way from achieving that, but I enlisted the help of the contributors to the Irish Conservatives Forum and we've put together a fairly good list now.

I'd like this to be the kind of blog post that people might find through an internet search. My post on differences between Ireland and America seems to get quite a lot of that traffic, as does my review of Groundhog Day. I hope it might be useful to people, or at least interesting.

What is a tradition? What is an Irish tradition? Two big questions. I don't have any working definition, but I've followed a few guidelines. I've tried to stick to traditions that are ongoing, or that might possibly be revived. (There are exceptions.) I've tried to stick to things that are distinctively Irish, though not necessarily exclusively Irish. That's pretty much it.

So, without any further ado, here is the list. If you can think of any traditions I've left out, please tell me.

Sport

Gaelic Football

Hurling

The Munster Hurling Final

Rounders

Road bowling

Rugby, especially in Limerick

Boxing

Horse racing and horse breeding

Supporting English soccer teams

The John 3:7 placard that sports fan carries to games

Swimming in the "forty-foot" promontory in Dublin Bay, especially on Christmas Day.

Making speeches after winning the All-Ireland

The social media hashtag #COYBIG (Come On You Boys in Green) when Ireland play international soccer matches

Music and Dance

Irish traditional music

Sean-nós singing

Irish folk ballads

Tin whistle

Uileann pipes

Lilting

Ceilidhs

Set dancing

Lúibíní, whatever the hell they are

Country music, in some areas. (I hear it is a way of life in some towns. Is that true?)

The Sean Ó Riada Mass, and the hymns taken from it

Handel's Messiah, first performed in Dublin and often performed there since

Language

The Irish language

Shelta

The various dialects

Yola and Old Fingalian (well, these are more memories than traditions, but I'll put them in anyway-- vanished dialects of English in the East of Ireland.

Hiberno-English, which deserves a section all of its own

Sculpture

Giving rhyming names to Dublin statues (the Floozy in the Jacuzzi, the pr---- with the sick, the hags with the bags, the tart with the cart, etc.) No name for the Millennium Spire ever stuck, despite many efforts. Also used for at least one monument in Belfast; "the Balls in the Falls".

Visual arts and architecture

Celtic knotwork

Pre-Celtic spirals

Hiberno-Romanesque architecture

John Hinde postcards

Ireland's strong tradition of stained glass, in the modern era

Round towers

Literature

The Irish literary tradition in general.

Short-story writing (Sean O'Faolain, Mary Lavin, and others.)

Winning the Nobel Prize for literature (four times)

The Ogham script of medieval Ireland

Food and Drink

Corned beef, cabbage and potatoes

A full Irish breakfast

Colcannon on Halloween

Red, white and orange ice-cream and jelly on St. Patrick's Day

Barmbrack

Tea. Strong tea, especially in rural areas. Lyons and Barry's.

Irish whiskey

Red lemonade

Cadet Orange

Cavan Cola. (I understand this is no longer produced but there are campaigns to revive it, so I will keep it in.)

Guinness

Irish stew

Dublin coddle

Friend breakfast at Bewley's

Dulsk (chewable seaweed)

Poteen

Politics

Catch-all parties

Clientelism and parish pump politics

The two-and-a-half party system

Small, breakaway parties that are successful for a while and then disappear

Splits. ("The first item on the agenda of every Irish organization is the split.")

Political dynasties and family

Broadcasting

The Late-Late Toy Show

The Late Late Show itself

The dawn chorus on Mooney Goes Wild

Dustin the turkey

Shows in the format of Scrap Saturday

Events

Bloomsday

The Rose of Tralee

The Galway Races

The Ploughing Championships

The Young Scientist Awards

St. Patrick's Day

Nollaig na mBan/Little Christmas

St. Brigit's Day

The summer solstice in Newgrange

The Twelfth of July

Reek Sunday

St. Patrick's Day parade, including the wearing of St. Patrick's Day shamrock

Halloween (an Irish tradition itself)

Mummery - the tradition of playing practical jokes and pranks for the sake of personal honour among young men. May just be an Ulsterian or Co.Louth variation, as I Mummery is the name of another, entirely different practice elsewhere in Ireland involving people stuffing straw up their shirts.

Halloween bonfires

Halloween costumes

Pumpkin carving (originally turnip carving.)

Death

The Irish wake

"I'm sorry for your troubles"

Education

The "debs"

The colours debate between Trinity and UCD

Social Life

Pretending not to see famous people

Apologizing

"You're very good", an expression equivalent to "Thank you"

The Irish mammy-- matriarch in working class areas (at least she used to be)

Wren boys

Irish names such as Sinéad, Cormac, etc.

Going to the Gaeltacht

Shops having later opening hours on Thursday nights (in Dublin at least-- not sure about elsewhere)

Religion

Standing at the back of church at Mass

Taking the straw from the Christmas crib

The Irish monastic tradition

First Communion madness

St. Brigid's Cross

St. Patrick's Day being a "break" from Lent

Calling the day after Christmas St. Stephen's Day (not Boxing Day, as in Commonwealth countries)

Lough Derg pilgrimage

Croagh Patrick pilgrimage

Sitting on the backmost kneelers during the 'sitting down' portions of Mass, then standing and kneeling at the appropriate parts, since its wrong to sit on the floor and it doesn't 'make sense' to be standing all the time when there's a perfectly good seat right there.

Superstitions

Burning the Jack of a newly bought/opened pack of cards because it's bad luck.

Not killing spiders because they are 'lucky' in the sense that they 'prevent' bad luck by killing pests such as flies and other lesser insects. I think this might just be an Ulsterian superstition.

Not picking up a comb left lying on the ground, as it may belong to a banshee.

Folk cures, including holy wells

Travelling to the house of a person with a healing prayer, for ailments such as a wart, having their hands raised over you and a prayer said by them, then being directed to a well to apply some of the well water. Certainly in Wicklow, possibly Cavan and Leitrim.

Clothes and jewellery

Aran sweaters

Cloth caps

Tara brooch replicas

Claddagh ring

The Irish language fáinne (ring-brooch), indicating you speak Irish

Pioneer pins

Trench coats

Lace-making, especially in particular areas such as Carrickmacross

Folklore

Banshees

Fairy forts and the Shee in general

Tir na nÓg

The Hell Fire Club in the Dublin mountains, and the legends attached to it

The Ulster Cycle

The Fae

The Children of Lir

The Book of Invasions

The Otherwold, including Tir Na n-Óg

Names

Nicknaming people named Christopher "Git"

The nickname "Joxer"

Men with the middle name "Mary", in honour of our Blessed Mother-- very popular once upon a time, and not so long ago

Transport

Aer Lingus vs. Ryanair

The Morris Minor

Miscelleanous

Carroll's cigarettes (still made?)

Bórd na Mona peat briquettes

President's cheque to centenarians

Begrudgery

The Irish weather, and talking about the weather

The Irish diaspora

Red hair

Blue eyes

Sunburn

Freckles

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

Conservatives in Trinity College Dublin!

Conservative students in Trinity College Dublin have started a conservative online journal, The Burkean Journal.

This is a very heartening development. It deserves support. I've glanced through its articles, and I see that it's not just cheap libertarianism, either-- there is an article defending populism, an article by a prolife activist, and an article defending Catholic history!

Hurray! A reason to be cheerful! Thanks, TCD conservatives!

This is a very heartening development. It deserves support. I've glanced through its articles, and I see that it's not just cheap libertarianism, either-- there is an article defending populism, an article by a prolife activist, and an article defending Catholic history!

Hurray! A reason to be cheerful! Thanks, TCD conservatives!

Sunday, September 17, 2017

Five Things Not to Say to an Introvert

Since the internet is full of consciousness-raising lists, and tips on how NOT to speak to various demographics, I thought I'd get in on the act. Here are five things not to say to an introvert, by a lifelong introvert.

1) "Can you ring me back?"

Please remember that an introvert is seriously messed up. Simple things like making a telephone call become a big deal. I know-- it's pathetic. It really is pathetic! The simple act of picking up a receiver, dialling a number, and talking to a disembodied voice makes an introvert's heart pound. Yes, this is very lame. But you're better off emailing.

2) "I'd better mingle."

A normal person, at a coffee morning or a reception, tries to speak to as many people as possible, and not linger over any one person. An introvert, who dreads approaching other human beings, latches onto someone and won't let go.

Come to think of it, you should probably be brutal, or you'll never get rid of him.

3) "Just ask the bus driver for directions."

Uh oh! Here again is something that seems straighforward. Bus drivers are used to being asked for directions. Does that make any difference to the introvert? No! He doesn't care about logic or rationality. He'll do anything to avoid such interactions.

Let's delve a little deeper into the insane pseudo-logic of the introvert here. He has no problem, say, walking up to a bar and asking for a brandy, because he knows that this is the primary function of a bar. But giving directions isn't the primary function of a bus driver, so he feels weird about it. Does that make sense? Of course it doesn't! He's a basket case!

4) "Did you get away on holiday this year?"

Introverts have a thing about small-talk. They hate it! And you know, this time the introvert is right and you're the obnoxious one. "Did you get away on holidays this year?" Really, is that the best you can do? You may as well say: "I can't avoid not talking to you, but I'm going to be as unimaginative and impersonal as possible. You're really not worth any more effort, any more risk than that". There are a hundred million more original and interesting things you can say. Are you trying to save the batteries on your imagination? You make me sick!

5) "Let's get out of our comfort zones."

The introvert would spend all his time in his comfort zone if he could. He doesn't find anything bracing or exciting about getting out of it. What you are saying to him is tantamount to: "Let's get cold, uncomfortable, wet, and hungry, hurray!". Why is he like this? Because he's messed up! If you take pity on him, you should certainly drag him out of his stagnation, but don't use the term "comfort zone" or you'll freak him out.

All this is deeply, deeply tragic. If you have an introverted child, beating the introversion out of it from an early age is recommended. It may not work, but it will help you to deal with some of the frustrations you'll experience.

In the future, we may be able to block the gene which causes introversion, preventing untold misery (and a great deal of bad poetry) in the future. In the meantime, you should probably try to be patient with any introverts you encounter-- you have no idea of the effort they are making, the unseen ordeals they go through.

But once they start talking about their "rich interior life", shut them up as quick as you can. You'll never hear the end of it otherwise.

1) "Can you ring me back?"

Please remember that an introvert is seriously messed up. Simple things like making a telephone call become a big deal. I know-- it's pathetic. It really is pathetic! The simple act of picking up a receiver, dialling a number, and talking to a disembodied voice makes an introvert's heart pound. Yes, this is very lame. But you're better off emailing.

2) "I'd better mingle."

A normal person, at a coffee morning or a reception, tries to speak to as many people as possible, and not linger over any one person. An introvert, who dreads approaching other human beings, latches onto someone and won't let go.

Come to think of it, you should probably be brutal, or you'll never get rid of him.

3) "Just ask the bus driver for directions."

Uh oh! Here again is something that seems straighforward. Bus drivers are used to being asked for directions. Does that make any difference to the introvert? No! He doesn't care about logic or rationality. He'll do anything to avoid such interactions.

Let's delve a little deeper into the insane pseudo-logic of the introvert here. He has no problem, say, walking up to a bar and asking for a brandy, because he knows that this is the primary function of a bar. But giving directions isn't the primary function of a bus driver, so he feels weird about it. Does that make sense? Of course it doesn't! He's a basket case!

4) "Did you get away on holiday this year?"

Introverts have a thing about small-talk. They hate it! And you know, this time the introvert is right and you're the obnoxious one. "Did you get away on holidays this year?" Really, is that the best you can do? You may as well say: "I can't avoid not talking to you, but I'm going to be as unimaginative and impersonal as possible. You're really not worth any more effort, any more risk than that". There are a hundred million more original and interesting things you can say. Are you trying to save the batteries on your imagination? You make me sick!

5) "Let's get out of our comfort zones."

The introvert would spend all his time in his comfort zone if he could. He doesn't find anything bracing or exciting about getting out of it. What you are saying to him is tantamount to: "Let's get cold, uncomfortable, wet, and hungry, hurray!". Why is he like this? Because he's messed up! If you take pity on him, you should certainly drag him out of his stagnation, but don't use the term "comfort zone" or you'll freak him out.

All this is deeply, deeply tragic. If you have an introverted child, beating the introversion out of it from an early age is recommended. It may not work, but it will help you to deal with some of the frustrations you'll experience.

In the future, we may be able to block the gene which causes introversion, preventing untold misery (and a great deal of bad poetry) in the future. In the meantime, you should probably try to be patient with any introverts you encounter-- you have no idea of the effort they are making, the unseen ordeals they go through.

But once they start talking about their "rich interior life", shut them up as quick as you can. You'll never hear the end of it otherwise.

Saturday, September 16, 2017

Slow News

Here are the current headlines on RTE's website:

FG open up eight-point lead over FF, latest poll shows.

Man arrested in connection with London Tube bombing.

Ryanair say flights cancelled due to messed-up holidays.

Sniffer dog Scooby discovers 230 K worth of cannabis.

U2 cancel St. Louis concert over safety concerns.

Arnotts evacuated after fire breaks out in store.

Search for man swept into sea while fishing in Co. Clare.

With all due respect to the man who fell into sea, and hopes that he is found, I find such "slow news days" immensely soothing and comforting. Not just now, when North Korea is firing missiles all over the place and Islamic terrorism is rampant, but all the time. I take an aesthetic pleasure from them. They are to the calendar what uncelebrated, ordinary towns and villages are to the map.

I have a nasty cold and I've been lying in bed for hours, so I have time to think about such things.

FG open up eight-point lead over FF, latest poll shows.

Man arrested in connection with London Tube bombing.

Ryanair say flights cancelled due to messed-up holidays.

Sniffer dog Scooby discovers 230 K worth of cannabis.

U2 cancel St. Louis concert over safety concerns.

Arnotts evacuated after fire breaks out in store.

Search for man swept into sea while fishing in Co. Clare.

With all due respect to the man who fell into sea, and hopes that he is found, I find such "slow news days" immensely soothing and comforting. Not just now, when North Korea is firing missiles all over the place and Islamic terrorism is rampant, but all the time. I take an aesthetic pleasure from them. They are to the calendar what uncelebrated, ordinary towns and villages are to the map.

I have a nasty cold and I've been lying in bed for hours, so I have time to think about such things.

Do Black Lives Matter, or Do All Lives Matter?

The obvious answer to this is "both", but it would be completely missing the point.

I've been thinking about this a lot recently. I don't mean the controversy about these two slogans, particularly. I mean the fact that so much of social and political controversy comes down to rhetoric, and so much of rhetoric comes down to emphasis.

The "black lives matter" crowd insist on "black lives matter", not because they don't believe that all lives matter-- let's ignore the question of the unborn child, for the sake of argument-- but because they think the value of black lives has been neglected, that it needs to be emphasised.

The "all lives matter" crowd respond with their own slogan, not because they don't think black lives matter, but because they feel that there has been quite enough emphasis on identity politics already.

This principle very much applies to controversies within the Catholic Church.

Personally, I'm entirely in favour of social justice, and I think there is such a thing as social justice-- I don't think justice is simply "fair dealing", one person not defrauding or robbing another.

But it often seems as though social justice has become the whole of Catholic teaching, that all bishops and religious orders and Catholic spokespeople ever talk about is racism, immigration, working conditions, housing, etc. etc.

Even accepting that our Faith is based upon Tradition as well as Scripture, the lack of interest that Jesus shows in politics is startling. "Who made me a judge over you to decide such things as that?". "Give unto Caesar that which belongs to Caesar". "My kingdom is not of this world."

Given this, is it so strange that I resent any further pandering to the "social justice crowd", that I'm reluctant to join in their rhetoric in any way? We have more than enough of it!

In the same way, it seems to me perfectly healthy that Catholics resent the lack of emphasis put upon the principle "No salvation outside the Church". The Wikipedia article on this subject shows us how often this has been affirmed, and how stridently, in the history of the Church's teaching Magisterium.

As well all know, it was reframed in a rather less strident form by the Second Vatican Council, but it wasn't abolished. And yet, how would anyone walking into a church today, or reading a Catholic magazine, or looking at a Catholic TV show, possibly realize that the Church is the ark of salvation, and not simply a "faith tradition"?

Is it really so strange that many Catholics are dstraught, today, that rhetoric that has been softened out of all recognition is being softened further, that doctrine that had been so de-emphasized is being de-emphasized even further? We might call the controversies raging in the Church today "emphasis wars", and personally I think they are entirely legitimate.

I've been thinking about this a lot recently. I don't mean the controversy about these two slogans, particularly. I mean the fact that so much of social and political controversy comes down to rhetoric, and so much of rhetoric comes down to emphasis.

The "black lives matter" crowd insist on "black lives matter", not because they don't believe that all lives matter-- let's ignore the question of the unborn child, for the sake of argument-- but because they think the value of black lives has been neglected, that it needs to be emphasised.

The "all lives matter" crowd respond with their own slogan, not because they don't think black lives matter, but because they feel that there has been quite enough emphasis on identity politics already.

This principle very much applies to controversies within the Catholic Church.

Personally, I'm entirely in favour of social justice, and I think there is such a thing as social justice-- I don't think justice is simply "fair dealing", one person not defrauding or robbing another.

But it often seems as though social justice has become the whole of Catholic teaching, that all bishops and religious orders and Catholic spokespeople ever talk about is racism, immigration, working conditions, housing, etc. etc.

Even accepting that our Faith is based upon Tradition as well as Scripture, the lack of interest that Jesus shows in politics is startling. "Who made me a judge over you to decide such things as that?". "Give unto Caesar that which belongs to Caesar". "My kingdom is not of this world."

Given this, is it so strange that I resent any further pandering to the "social justice crowd", that I'm reluctant to join in their rhetoric in any way? We have more than enough of it!

In the same way, it seems to me perfectly healthy that Catholics resent the lack of emphasis put upon the principle "No salvation outside the Church". The Wikipedia article on this subject shows us how often this has been affirmed, and how stridently, in the history of the Church's teaching Magisterium.

As well all know, it was reframed in a rather less strident form by the Second Vatican Council, but it wasn't abolished. And yet, how would anyone walking into a church today, or reading a Catholic magazine, or looking at a Catholic TV show, possibly realize that the Church is the ark of salvation, and not simply a "faith tradition"?

Is it really so strange that many Catholics are dstraught, today, that rhetoric that has been softened out of all recognition is being softened further, that doctrine that had been so de-emphasized is being de-emphasized even further? We might call the controversies raging in the Church today "emphasis wars", and personally I think they are entirely legitimate.

The Tunnel of Time

Every workday, I walk through a "tunnel" which leads from the John Henry Newman arts faculty building to the James Joyce Library. (Everyone calls it a tunnel, even though it's not underground. It's a glass-roofed covered walkway.) For a good few years now, the tunnel has had a series of exhibition panels, representing the history of University College Dublin and the concurrent history of Ireland, running along one side of it. Since UCD was founded in the 1850s, the timeline begins there, and it ends (for some reason) in 1970. Perhaps there are later panels somewhere else in the university.

Walking from the Newman Building to the library is walking through recent Irish history, and walking from the library to the Newman building is walking backwards through recent Irish history.

Anyone who has read this blog for any length of time can imagine my reactions to this display. The photographs inspire intense feelings of nostalgia, affection, belonging, loss and protectiveness in me.

In many ways, they are simply fascinating in themselves. The group photographs (of graduating classes, for instance) are poignant, as group photos always are. I was a part of a group photograph yesterday and they always make me feel a little strange. I think everybody must have the same reaction; scanning those rows of long-ago faces, you wonder what happened to them. Did they live long? Were they happy? What became of them?

From my point of view, the exhibition chronicles a tale of decline; from a robustly Catholic, traditionally-minded Ireland to the era of student radicalism and campus unrest.

Here, for instance, is an image of two men who embody the Bad Old Ireland of progressive historiography, flanking a papal nuncio of some sort; Archbishop John Charles McQuaid on the left, and President Eamon De Valera on the right. I know it's a small picture, but just look at the sheer confidence with which they stride down the street. They are in charge and they know it.

One of the interesting things about the rise of the Alt Right is the rehabilitation of the idea of patriarchy. Suddenly, there are dozens of gorgeous young women queuing up to post YouTube videos in which they heap praise on patriarchy. Not so long ago, the seventeenth-century English philosopher Robert Filmer, whose Patriarcha defended the divine right of kings based upon the authority of fathers, seemed an example of an utterly obsolete concept, a footnote in intellectual history. Perhaps not so, after all.

I wouldn't call myself a believer in patriarchy, since it summons up images of women barefoot and pregnant in the kitchen, but I will admit that, in my heart, I want a country to be run by old men-- a gerontocracy, as well as a patriarchy. It seems right and natural. Perhaps this is because the wise old man is an archetype. I don't know. Anyway, the exhibition is full of grey-haired, suited, anti-charismatic old men, and I greatly approve of this! (Perhaps this is another reason I am interested in later Soviet Russia-- it was a gerontocracy to a notorious degree.)

Of course, De Valera and John Charles McQuaid are admirable for more than just being old men. They were both reactionaries of the highest calibre. De Valera used the occasion of the very first television broadcast in Ireland to voice anxieties about the new technology. And how right he was! McQuaid agitated against mixed male-and-female athletics, organized a boycott of an Ireland-Yugoslavia soccer game to protest persecution of the Church in Yugoslavia, and told the Irish faithful at the end of Vatican II: "“You may, in the last four years, have been disturbed by reports about the council . . . You may have been worried by talk of changes to come. Allow me to reassure you: no change will worry the tranquillity of your Christian lives.” How wrong he was! But if only he had been right!

However, if I don't proceed down the tunnel, I will be late for work.

Here is a picture of veteran's of Jacob's Biscuit Factory, one of the garrisons of the 1916 Rising. (American readers, please note that biscuits in Ireland are what you call "cookies").

Look how dignified they are, how assured of their place in history! The revisionist historiography of the 1916 Rising had yet to be written.

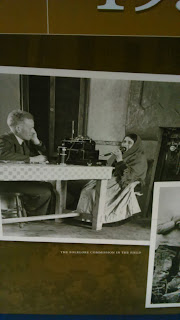

Here is my favourite picture of the exhibition: a UCD historian collects folklore from an old peasant woman.

I love, love, love this picture. It depicts a healthy ordering of values, in my view; the sober, scholarly, dark-suited historian is listening, deferentially, to the simple peasant woman. She is the repository of the nation's folklore, its greatest riches, its very soul. "Backwardness" is, in fact, the right way round. This is my idea of romantic nationalism.

Here is Patrick Kavanagh, the poet, who gave some lectures on poetry in UCD. On this blog, I've often quoted his line: "Through a chink too wide there comes in no wonder", which I consider one of the profoundest lines of poetry ever written. Sadly, he was a basher of cultural nationalism, or "bucklepping" as he called it.

Uh-oh, here's trouble! He is Noel Browne, an Irish politician with communist tendencies who was a fanatical enemy of the Catholic Church. Although he did good work in fighting the TB epidemic of the nineteen-fifties, he was an extremely bitter and egotistical man, a fact acknowledged even by his allies. He was famous for his confrontation with the Irish hierarchy over the Mother and Child Scheme, by which the State would provide free care for mothers and infants to a certain age. When I was taught about this in school (Catholic school!) the reasons for the hierarchy's opposition was left utterly mysterious. I presumed it had something to do with sex, or breastfeeding, or something like that. In reality, the Church was concerned at the power being given to the State, and its intrusion into the life of the family. Hard to imagine it today, when Catholic prelates answer to everything seems to be ever-more government. (And I'm not a libertarian by any means.) Here he is seen protesting outside the American Embassy at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Here is a picture of Butch Moore, who represented Ireland in the first Eurovision Song Contest we entered, in 1965. I don't know if Americans know about the Eurovision Song Contest. It's a competition in which TV networks from various European countries enter one song each, and one song is chosen as the winner-- formerly by voting panels, now by the public. It's how Abba got their big break. Ireland has won it more often than any other country. People like to make affectionate fun of it; the songs are usually very cheesy. I have happy memories of watching it with my brother and mother; we would buy fizzy drinks and treats for it, it was a little occasion. The voting is much more fun than the music.

I included this picture because, although I'm such a backwards-looking person, I'm most nostalgic for relatively recent Irish history-- the sixties to the early nineties, perhaps. Ireland was still Catholic and nationalist, but recognizably modern. I can be nostalgic enough about the nineteen-thirties, but it's too foreign to really identify with. But I can imagine living in 1965, and I can remember living in 1985. I'd never heard of Butch Moore, but from the looks of him he seems a very respectable, wholesome kind of entertainer.

And now, onto decline and fall. You can get a broad view of it here, including the obligatory picture of the Beatles:

A little later, we get photos of students who are suddenly bolshie, preening, loutish, long-haired, sullen, and all the rest of it. There are other images of student radical magazines and posters, which I should have taken:

A sorry, dispiriting final destination.

When I conceived this blog post, I was mostly intending to write about nostalgia itself. I was going to acknowledge all its dangers and contradictions. However, it took a different direction, and now I realize that I don't want to do this. You've heard it all before. We've all heard it all before. Everything that can be said against nostalgia is pretty obvious, and is constantly said.

And to be honest, although I've written this post with something of an ironic tone, I've said nothing I don't sincerely believe.

There is one observation I'd like to make, and this is something that often strikes me as I walk past the exhibition. Has it ever occurred to you that the spirit of a nation and the spirit of a historical period, as concepts, are very similar? Liberals, deconstructionists, debunkers, and all those dreary people are always reminding us of heterogeneity, contradiction, complexity, and so forth. There is no "Ireland", they say. There was no "fifties", they say. And they would seem to have a case. There are so many elements to the life of a country, so many elements to the life of an era, that it seems a vain effort to distill some kind of essence from it all.

E pur si muove...Somehow, in spite of all this, there is a spirit of an age, there is a spirit of a nation. You only have to look at a photograph from a particular time to see it. I won't claim you only have to look at a photograph from a particular country to see it-- you might have to watch a TV broadcast, or read a newspaper. It's more diffuse, but it's there.

In the case of a historical period, it takes a distance of years to see it. Take a picture today, and put it away for thirty years. Suddenly you'll see something in it that wasn't there the first time you looked at it. Now, this moment in history.

One of my most vivid memories of America is from the second or third time I visited. On my first visits, I'd been so eager to experience Americana that I'd been disappointed. Nothing seemed all that different. Then, on this particular visit, as I was sitting in Philadelphia airport, I looked up from my book and was suddenly hit by the American-ness of everything like steam from a sauna.

However, this doesn't make me complacent. I'm still anxious for the national distinctiveness of every country. I think the phrase: "There's no there there" is one of the most profound ever uttered. Looking at the exhibition panels in UCD's tunnel of time, I'm struck by the fact there's much more of a there in the earlier pictures-- the ones closest to the Gaelic Revival. I want more there for Ireland, not less. In fact, I want that for the entire world.

Walking from the Newman Building to the library is walking through recent Irish history, and walking from the library to the Newman building is walking backwards through recent Irish history.

Anyone who has read this blog for any length of time can imagine my reactions to this display. The photographs inspire intense feelings of nostalgia, affection, belonging, loss and protectiveness in me.

In many ways, they are simply fascinating in themselves. The group photographs (of graduating classes, for instance) are poignant, as group photos always are. I was a part of a group photograph yesterday and they always make me feel a little strange. I think everybody must have the same reaction; scanning those rows of long-ago faces, you wonder what happened to them. Did they live long? Were they happy? What became of them?

From my point of view, the exhibition chronicles a tale of decline; from a robustly Catholic, traditionally-minded Ireland to the era of student radicalism and campus unrest.

Here, for instance, is an image of two men who embody the Bad Old Ireland of progressive historiography, flanking a papal nuncio of some sort; Archbishop John Charles McQuaid on the left, and President Eamon De Valera on the right. I know it's a small picture, but just look at the sheer confidence with which they stride down the street. They are in charge and they know it.

One of the interesting things about the rise of the Alt Right is the rehabilitation of the idea of patriarchy. Suddenly, there are dozens of gorgeous young women queuing up to post YouTube videos in which they heap praise on patriarchy. Not so long ago, the seventeenth-century English philosopher Robert Filmer, whose Patriarcha defended the divine right of kings based upon the authority of fathers, seemed an example of an utterly obsolete concept, a footnote in intellectual history. Perhaps not so, after all.

I wouldn't call myself a believer in patriarchy, since it summons up images of women barefoot and pregnant in the kitchen, but I will admit that, in my heart, I want a country to be run by old men-- a gerontocracy, as well as a patriarchy. It seems right and natural. Perhaps this is because the wise old man is an archetype. I don't know. Anyway, the exhibition is full of grey-haired, suited, anti-charismatic old men, and I greatly approve of this! (Perhaps this is another reason I am interested in later Soviet Russia-- it was a gerontocracy to a notorious degree.)

Of course, De Valera and John Charles McQuaid are admirable for more than just being old men. They were both reactionaries of the highest calibre. De Valera used the occasion of the very first television broadcast in Ireland to voice anxieties about the new technology. And how right he was! McQuaid agitated against mixed male-and-female athletics, organized a boycott of an Ireland-Yugoslavia soccer game to protest persecution of the Church in Yugoslavia, and told the Irish faithful at the end of Vatican II: "“You may, in the last four years, have been disturbed by reports about the council . . . You may have been worried by talk of changes to come. Allow me to reassure you: no change will worry the tranquillity of your Christian lives.” How wrong he was! But if only he had been right!

However, if I don't proceed down the tunnel, I will be late for work.

Here is a picture of veteran's of Jacob's Biscuit Factory, one of the garrisons of the 1916 Rising. (American readers, please note that biscuits in Ireland are what you call "cookies").

Look how dignified they are, how assured of their place in history! The revisionist historiography of the 1916 Rising had yet to be written.

Here is my favourite picture of the exhibition: a UCD historian collects folklore from an old peasant woman.

I love, love, love this picture. It depicts a healthy ordering of values, in my view; the sober, scholarly, dark-suited historian is listening, deferentially, to the simple peasant woman. She is the repository of the nation's folklore, its greatest riches, its very soul. "Backwardness" is, in fact, the right way round. This is my idea of romantic nationalism.

Here is Patrick Kavanagh, the poet, who gave some lectures on poetry in UCD. On this blog, I've often quoted his line: "Through a chink too wide there comes in no wonder", which I consider one of the profoundest lines of poetry ever written. Sadly, he was a basher of cultural nationalism, or "bucklepping" as he called it.

Uh-oh, here's trouble! He is Noel Browne, an Irish politician with communist tendencies who was a fanatical enemy of the Catholic Church. Although he did good work in fighting the TB epidemic of the nineteen-fifties, he was an extremely bitter and egotistical man, a fact acknowledged even by his allies. He was famous for his confrontation with the Irish hierarchy over the Mother and Child Scheme, by which the State would provide free care for mothers and infants to a certain age. When I was taught about this in school (Catholic school!) the reasons for the hierarchy's opposition was left utterly mysterious. I presumed it had something to do with sex, or breastfeeding, or something like that. In reality, the Church was concerned at the power being given to the State, and its intrusion into the life of the family. Hard to imagine it today, when Catholic prelates answer to everything seems to be ever-more government. (And I'm not a libertarian by any means.) Here he is seen protesting outside the American Embassy at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Here is a picture of Butch Moore, who represented Ireland in the first Eurovision Song Contest we entered, in 1965. I don't know if Americans know about the Eurovision Song Contest. It's a competition in which TV networks from various European countries enter one song each, and one song is chosen as the winner-- formerly by voting panels, now by the public. It's how Abba got their big break. Ireland has won it more often than any other country. People like to make affectionate fun of it; the songs are usually very cheesy. I have happy memories of watching it with my brother and mother; we would buy fizzy drinks and treats for it, it was a little occasion. The voting is much more fun than the music.

I included this picture because, although I'm such a backwards-looking person, I'm most nostalgic for relatively recent Irish history-- the sixties to the early nineties, perhaps. Ireland was still Catholic and nationalist, but recognizably modern. I can be nostalgic enough about the nineteen-thirties, but it's too foreign to really identify with. But I can imagine living in 1965, and I can remember living in 1985. I'd never heard of Butch Moore, but from the looks of him he seems a very respectable, wholesome kind of entertainer.

And now, onto decline and fall. You can get a broad view of it here, including the obligatory picture of the Beatles:

A little later, we get photos of students who are suddenly bolshie, preening, loutish, long-haired, sullen, and all the rest of it. There are other images of student radical magazines and posters, which I should have taken:

A sorry, dispiriting final destination.

When I conceived this blog post, I was mostly intending to write about nostalgia itself. I was going to acknowledge all its dangers and contradictions. However, it took a different direction, and now I realize that I don't want to do this. You've heard it all before. We've all heard it all before. Everything that can be said against nostalgia is pretty obvious, and is constantly said.

And to be honest, although I've written this post with something of an ironic tone, I've said nothing I don't sincerely believe.

There is one observation I'd like to make, and this is something that often strikes me as I walk past the exhibition. Has it ever occurred to you that the spirit of a nation and the spirit of a historical period, as concepts, are very similar? Liberals, deconstructionists, debunkers, and all those dreary people are always reminding us of heterogeneity, contradiction, complexity, and so forth. There is no "Ireland", they say. There was no "fifties", they say. And they would seem to have a case. There are so many elements to the life of a country, so many elements to the life of an era, that it seems a vain effort to distill some kind of essence from it all.

E pur si muove...Somehow, in spite of all this, there is a spirit of an age, there is a spirit of a nation. You only have to look at a photograph from a particular time to see it. I won't claim you only have to look at a photograph from a particular country to see it-- you might have to watch a TV broadcast, or read a newspaper. It's more diffuse, but it's there.

In the case of a historical period, it takes a distance of years to see it. Take a picture today, and put it away for thirty years. Suddenly you'll see something in it that wasn't there the first time you looked at it. Now, this moment in history.

One of my most vivid memories of America is from the second or third time I visited. On my first visits, I'd been so eager to experience Americana that I'd been disappointed. Nothing seemed all that different. Then, on this particular visit, as I was sitting in Philadelphia airport, I looked up from my book and was suddenly hit by the American-ness of everything like steam from a sauna.

However, this doesn't make me complacent. I'm still anxious for the national distinctiveness of every country. I think the phrase: "There's no there there" is one of the most profound ever uttered. Looking at the exhibition panels in UCD's tunnel of time, I'm struck by the fact there's much more of a there in the earlier pictures-- the ones closest to the Gaelic Revival. I want more there for Ireland, not less. In fact, I want that for the entire world.

Thursday, September 14, 2017

Just a Statistic

Now and again, I look at the blog of Bruce Charlton, an English academic and Christian, who is one of the few commentators out there who appreciates the seriousness of political correctness. I discovered him when I went looking for books about PC and bought his little volume Thought Prison. He's very much an original. (He once commented on this blog.)

His recent blog post on the decline in his blog statistics gave me much food for thought.

Professor Charlton is still averaging around two thousand hits a day. It's such a contrast to my own statistics.

Since I started it in 2011, this blog has accumulated 420,829 pageviews. That seems like a lot, in absolute terms, but I don't know if it's such a lot given the amount I've posted.

Last month, it received 9,536 pageviews. Yesterday, it received 184 pageviews. (At times, I average three hundred pageviews or so-- it goes up and down.)

In terms of my individual posts, their pageviews rarely reach triple figures. The review of It that I wrote on Saturday has had 101 pageviews so far. Most posts seem to settle at around 45 pageviews.

Compared to some of the YouTube vloggers I watch, these numbers are extremely small. For instance, my favourite YouTuber, Millennial Woes, has thirty thousand subscribes after four years. Admittedly, videos may be a lot more popular than blog posts.

On the other hand, I'm quite often surprised at how many people know about the blog. Strangers have recognized me through it. (Only once or twice, but it's happened.) A fair amount of people in Catholic circles in Ireland seem to know of it. it's included in the National Library of Ireland's web archive, for what that's worth.

And sometimes I'm surprised at how low blog readerships can be. I was taken aback when I learned that a well-regarded Irish library-themed blog doesn't have many more readers than this blog.

Well, I'm grateful people do read it. That can never be taken for granted. All writings exists to be read, and it means a lot that people out there do read what I write.

His recent blog post on the decline in his blog statistics gave me much food for thought.

Professor Charlton is still averaging around two thousand hits a day. It's such a contrast to my own statistics.

Since I started it in 2011, this blog has accumulated 420,829 pageviews. That seems like a lot, in absolute terms, but I don't know if it's such a lot given the amount I've posted.

Last month, it received 9,536 pageviews. Yesterday, it received 184 pageviews. (At times, I average three hundred pageviews or so-- it goes up and down.)

In terms of my individual posts, their pageviews rarely reach triple figures. The review of It that I wrote on Saturday has had 101 pageviews so far. Most posts seem to settle at around 45 pageviews.

Compared to some of the YouTube vloggers I watch, these numbers are extremely small. For instance, my favourite YouTuber, Millennial Woes, has thirty thousand subscribes after four years. Admittedly, videos may be a lot more popular than blog posts.

On the other hand, I'm quite often surprised at how many people know about the blog. Strangers have recognized me through it. (Only once or twice, but it's happened.) A fair amount of people in Catholic circles in Ireland seem to know of it. it's included in the National Library of Ireland's web archive, for what that's worth.

And sometimes I'm surprised at how low blog readerships can be. I was taken aback when I learned that a well-regarded Irish library-themed blog doesn't have many more readers than this blog.

Well, I'm grateful people do read it. That can never be taken for granted. All writings exists to be read, and it means a lot that people out there do read what I write.

RIP J.P. Donleavy

Reader, please me join me in a prayer for the soul of J.P. Donleavy, the Irish-American author whose death was announced today. Eternal rest grant unto him, oh Lord; may perpetual light shine upon him; may he rest in peace.

http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/news/acclaimed-author-jp-donleavy-dies-at-91-36130864.html

I was a big, big fan of J.P. Donleavy in my late teens and early twenties. I came upon his work by complete chance; somehow, a copy of De Alfonce Tennis, one of the strangest books I've ever read, happened to be knocking around the house. I've never been able to find out where it came from. De Alfonce Tennis is a book about a form of tennis which (I eventually learned) was actually played by Mr. Donleavy and his friends. The book is partly a novel, partly a humorous manual on the rules of the game and the way of life expected of its players. The protagonist is a fictionalized version of the author, and the narrative describes an ocean liner journey to America, during which he falls for a beautiful English woman named Laura. How I fell in love with Laura! She was the epitome of female desirability to my fourteen-year-old self; accomplished, intelligent, mysterious, pale-skinned, dark-haired. At one point, we are told that she had travelled to Tibet where she had been the only woman ever allowed to look at certain sacred texts. That was what I wanted women to be, at that age; awe-inspiring.

Laura and Jay Pee (as he is called in the book) play the first ever match of De Alfonce Tennis on board the liner. The game's court and rules are, as a result, full of nautical references. (The game's rules and equipment were bequeathed to the narrator by a mysterious "Founder"; I forget the exact details.)

Obviously, I recognized the book was a big leg-pull, but the surprising thing was that many of its passages were startlingly lyrical. I read them again and again

I went on to read other Donleavy books; his debut and most enduringly famous work, The Ginger Man, set in the bohemian fifties Dublin that he knew as an American student on the G.I. Bill; The Saddest Summer of Samuel S, a novella set in Vienna, which peers into the world of an eccentric expatriate whose life revolves around his psychoanalysis sessions; A Fairytale of New York, the meandering story of a free spirit in New York who spends time working in an undertaker's, amongst other things (if the title sounds familiar, it's because Shane MacGowan swiped it for his song); The Onion Eaters, a romp set in an aristocratic house in the Irish countryside, whose new owner is impoverished, and afflicted with a rash of house-guests, most of them uninvited; and a few others, which I didn't like as much as the ones I've named.

Donleavy was a complete original. His plots were not particularly inventive or imaginative, and his stories were rather shapeless; they often seemed to begin and end at random. But his prose was very often pure poetry. I remember being literally unable to sleep one night, at the age of sixteen, after reading The Saddest Summer of Samuel S, because I wanted so badly to write like J.P. Donleavy. At one point, my father accused me of hero-worshipping him!

One memorable feature of Donleavy's books were the little poems he would use to finish most chapters. Here is one example, from The Onion Eaters. (Please forgive the coarseness; Donleavy could be extremely bawdy).

As the circus continues

More crazy than cruel

One of us now

Will spin like a top

On the end of his tool.

Another notable feature of Donleavy's prose was that he would often put the verb at the end of a sentence, German-style, apparently for aesthetic effect alone. I don't have any examples to hand, but he would write something like: "I sauntered down Fifth Avenue, eager the city's giddy atmosphere to taste". I loved that. The idea of simply playing with language in this way intoxicated me.

I actually got to meet J.P. Donleavy, in 1998, when I was twenty-one. I wrote a fan letter to him, and asked if I could interview him for an article. He sent me a postcard, which I've carefully kept, inviting me to phone him, which I did. We arranged that I would travel down to his rather grand residence, Levington Park in Mullingar. I interviewed him for perhaps an hour and a half. I taped the interview. (I recently came across the cassette. I have nothing to play it on now, though. I'm not even sure it's playable after all this time.) The resulting article was published in Foinse, the Irish language newspaper. He was a very gentlemanly, down-to-earth fellow, not at all the eccentric I was expecting. He told me that one of the reasons he'd granted the interview was because I'd mentioned De Alfonce Tennis in my letter, a book that (he complained) most people simply ignored.

Well, that was then. In the nearly twenty years that have passed, I've often thought of sending him a Christmas card. Now it's too late. It's a long time since I've read his books, and I'm not sure I'll ever read them again. They belong to a particular moment in my life. But they were very important to me in my youth. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam.

http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/news/acclaimed-author-jp-donleavy-dies-at-91-36130864.html

I was a big, big fan of J.P. Donleavy in my late teens and early twenties. I came upon his work by complete chance; somehow, a copy of De Alfonce Tennis, one of the strangest books I've ever read, happened to be knocking around the house. I've never been able to find out where it came from. De Alfonce Tennis is a book about a form of tennis which (I eventually learned) was actually played by Mr. Donleavy and his friends. The book is partly a novel, partly a humorous manual on the rules of the game and the way of life expected of its players. The protagonist is a fictionalized version of the author, and the narrative describes an ocean liner journey to America, during which he falls for a beautiful English woman named Laura. How I fell in love with Laura! She was the epitome of female desirability to my fourteen-year-old self; accomplished, intelligent, mysterious, pale-skinned, dark-haired. At one point, we are told that she had travelled to Tibet where she had been the only woman ever allowed to look at certain sacred texts. That was what I wanted women to be, at that age; awe-inspiring.

Laura and Jay Pee (as he is called in the book) play the first ever match of De Alfonce Tennis on board the liner. The game's court and rules are, as a result, full of nautical references. (The game's rules and equipment were bequeathed to the narrator by a mysterious "Founder"; I forget the exact details.)

Obviously, I recognized the book was a big leg-pull, but the surprising thing was that many of its passages were startlingly lyrical. I read them again and again

I went on to read other Donleavy books; his debut and most enduringly famous work, The Ginger Man, set in the bohemian fifties Dublin that he knew as an American student on the G.I. Bill; The Saddest Summer of Samuel S, a novella set in Vienna, which peers into the world of an eccentric expatriate whose life revolves around his psychoanalysis sessions; A Fairytale of New York, the meandering story of a free spirit in New York who spends time working in an undertaker's, amongst other things (if the title sounds familiar, it's because Shane MacGowan swiped it for his song); The Onion Eaters, a romp set in an aristocratic house in the Irish countryside, whose new owner is impoverished, and afflicted with a rash of house-guests, most of them uninvited; and a few others, which I didn't like as much as the ones I've named.

Donleavy was a complete original. His plots were not particularly inventive or imaginative, and his stories were rather shapeless; they often seemed to begin and end at random. But his prose was very often pure poetry. I remember being literally unable to sleep one night, at the age of sixteen, after reading The Saddest Summer of Samuel S, because I wanted so badly to write like J.P. Donleavy. At one point, my father accused me of hero-worshipping him!

One memorable feature of Donleavy's books were the little poems he would use to finish most chapters. Here is one example, from The Onion Eaters. (Please forgive the coarseness; Donleavy could be extremely bawdy).

As the circus continues

More crazy than cruel

One of us now

Will spin like a top

On the end of his tool.