Monday, May 31, 2021

My Cinemania

Friday, May 28, 2021

A Blog Post by My Father

In our humble opinion, only time can determine what is or is not "Art". Contemporary art is a nonsense, only the judgement of the generations to come can bestow the "imprimatur". And it is our earnest wish that posterity will consign most modern art to the dustbin reserved for irrelevancies. Because, and we say this in all seriousness, if what passes for art today is still around fifty years hence, then western society will have become a jungle of which the most "red in tooth and claw" predator could be proud. As proof of what we say, consider the calibre of creative geniuses who would in all probability be turned down for Arts Counil funding if they made an appearance in Merrion Square in the morning.

Wednesday, May 19, 2021

My Favourite Opening Passage of All Time

I love books. I've always loved books. I'm most definitely a bibliophile, although I'm not a connoiseur. I don't particularly get excited about first editions or the quality of bindings. In fact, being irremediably plebeian, I've always preferred paperbacks to hardbacks. They're more comfortable to hold in your hands.

I'm not a fast reader, and I'm not as well-read as I'd like to be. I wish I'd spent much, much more time reading when I was a kid. But books have always excited me in a unique way.

Whenever I find myself in a new house, I always drift towards the bookshelves, and wish I could spend more time just silently scanning them. I can rarely pass a bookshop without stopping in it.

I'm fascinated by all the aspects of a book-- the title, the dedication, the acknowledgements, the publisher's logo, the introduction, and so on.

One of the aspects that fascinates me is the opening. The curtain is pulled away and we see out the window onto-- what? It could be anything. The author addresses us for the first time, and we hear his or her unique voice, coming to us from some other time and place.

Of course, there are many famous opening lines. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times." "Call me Ishmael". "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there." "Gaul is divided into three parts." And let's not forget the much-mocked but inimitable "It was a dark and stormy night."

There are some not-so-famous openings that have stuck with me, too. For instance, these opening lines from Clive Baker's dark fantasy novel Weaveworld (a thumping great book that I never actually finished), which I think are worth quoting at some length:

Nothing ever begins.

There is no first moment; no single word or place from which this or any other story springs.The threads can always be traced back to some earlier tale, and to the tales that preceded that: though as the narrator’s voice recedes the connections will seem to grow more tenuous, for each age will want the tale told as if it were of its own making.

Thus the pagan will be sanctified, the tragic become laughable; great lovers will stoop to sentiment, and demons dwindle to clockwork toys.

Nothing is fixed. In and out the, shuttle goes, fact and fiction, mind and matter, woven into patterns that may have only this in common: that hidden amongst them is a filigree which will with time become a world.

It must be arbitrary then, the place at which we chose to embark.

Somewhere between a past half forgotten and a future as yet only glimpsed.

This place, for instance.

Wednesday, May 5, 2021

My Latest Article in Ireland's Own

My latest article in Ireland's Own is "The Magic of Writing", and is (I hope) a breezy piece on the creative processes and working habits of writers. It's a subject that fascinates me. It appears in the May Annual, pictured here.

I've had quite a few articles published in Ireland's Own now. My first was about newspaper letter pages (incidentally, the subject on which I wrote my college dissertation), and appeared in March 2017. Since then I've had articles on a wide variety of subjects published in it: "Slogans in Irish Life", "The Weird and Wonderful World of Sports", a look back at the Dublin Millennium of 1988, a piece on streets named after Irish people all over the world, a Christmas piece on the ghost stories of M.R. James (traditionally told and broadcast at Christmas), and a few others.

I even had a fifteen-part series on Irish lighthouses! Boy, did that take a lot of research...

I'm proud to have my articles appear in Ireland's Own. It's almost the only "family" magazine widely sold in Ireland. It's also one of very the few general interest magazines available here. The magazine shelves in Ireland (as elsewhere, I fear) are dominated by glossy women's magazines, car magazines, TV soap magazines, and other magazines which could be best described as "consumer culture and lifestyle".

Ireland's Own is also a legacy of the Irish Revival, first appearing in 1902. I've heard it described as the only survivor of a raft of similar publications which first appeared at that time.

I have happy childhood memories of reading Ireland's Own. My aunt Kitty, who lived on a farm in Limerick, had stacks of past issues. I particularly enjoyed the ghost stories. The long-running column "Stranger Than Fiction", which chronicled stories of the uncanny, gave me many pleasant chills. It's still running today!

My aunt Kitty died in 2007, but her husband is still alive. I actually only learned this very recently, and I spoke to him (on the phone) a few days ago, for the first time since my wedding in 2013. He's just turned eighty-nine. When I was a kid, summer holidays were spent on his farm in Limerick. It was a huge contrast to Ballymun and made a big impression on me. It seemed quite obvious to me that rural life and rural ways were healthier than those of the housing estate where I lived.

It even led me to a (brief) religious conversion at the age of fourteen. Mass attendance was already dropping in Dublin at this time, so it was a new and arrresting experience to see a whole village attend Mass together. The gospel text that sparked my imagination was "I am the vine, you are the branches"...which, coincidentally, is also today's gospel text. My newfound piety didn't last long on my return to Dublin, however.

When I went to my aunt's funeral in 2007, I was becoming increasingly conservative and traditional. I'd always been something of a cultural conservative, especially when it came to poetry and visual art. But, by this time, I was moving more towards social conservatism, as well. I remember standing in the church at my aunt's funeral-- the same church where I'd had my fleeting conversion-- and feeling a powerful inner conflict. I could see clearly by now that the Catholic Church was the protector of so much that I found precious, but I couldn't simply believe on this account. It took a lot of thinking and reading and (I might even say) agonizing to take that final step.

Recently, as I mentioned a few weeks ago, an elderly gentleman who I knew somewhat passed away. I had been meaning to get back in touch with him for many months. When I finally emailed him, and got no reply, I discovered I'd been too late by a matter of weeks. This motivated me to get in touch with my uncle, and I was overjoyed that the case was different this time. Deo gratias!

Wednesday, April 28, 2021

Why I Am a Humanist

I've been very busy recently, or at least very occupied. So, to keep the blog ticking over, here is an article that I had published in the Catholic Voice newspaper in 2014.

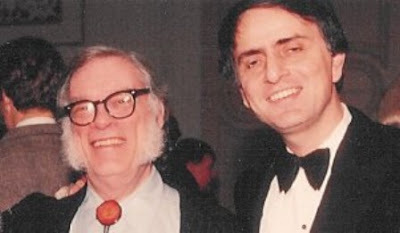

A Much-Vexed WordWhat did Carl Sagan, Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov and Jean Paul Sartre all have in common? Your first answer might be, “They were all atheists”, and that would certainly be true. But another thing they have in common is that they are all listed on the website of the Humanist Association of Ireland as famous humanists.

|

| Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan |

It would seem, according to this organisation, that a humanist is necessarily an atheist. Indeed, their description of humanism makes this clear: “Humanism is a view of life that combines reason with compassion. It is based on a concern for humanity in general, and for human individuals in particular. It is for people who base their interpretation of existence on the evidence of the natural world and its evolution, and not on belief in the supernatural (theistic god, miracles, afterlife, revealed morality etc.).”

So, can you be a humanist but not an atheist? And can a Christian be a humanist?

Jacques Maritain, the famous twentieth century Catholic philosopher, would certainly have answered “Yes!” to both questions. His book Integral Humanism greatly influenced the Christian Democratic movement in Europe. He also helped to draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Other Christians who are often considered to be humanists include St. John Paul II (who subscribed to a philosophy called personalism, which is a form of humanism), Dante, Chaucer, G.K. Chesterton, John Henry Newman, T.S. Eliot, and Pope Paul VI, whose closing address to the Second Vatican Council included these words: “We call upon those who term themselves modern humanists, and who have renounced the transcendent value of the highest realities, to give the council credit at least for one quality and to recognise our own new type of humanism: we, too, in fact, we more than any others, honour mankind.”

Does the question even matter? I think it does. As somebody who considers himself both a Catholic and a humanist, I believe that Christians should resist the efforts of secular humanists to take ownership of this term. I believe that nobody has a better entitlement to it than followers of Jesus Christ, since Christ (as we believe) chose to become human, told us that the Sabbath was made for man and not man for the Sabbath, and assured us that every hair on our heads has been counted.

What is Humanism?

Historically speaking, humanism has nothing at all to do with atheism. The universally recognised ‘Father of Humanism’ is Petrarch, the Italian poet who died in 1374. Petrarch was a devout Catholic whose interest in ancient Greece and Rome helped to bring about the Renaissance. Later on, Desiderius Erasmus and St. Thomas More both earned the title ‘humanist’, on account of their immersion in the classical past and their emphasis upon human reason. Both, of course, remained loyal Catholics—Erasmus refusing to join Luther’s rebellion against the Pope, and St. Thomas More sacrificing his life to defend the independence of the Church from the State.

What, then, is humanism?

The Oxford English Dictionary online offers three different definitions, and they are interestingly diverse. Here they are: “A rationalistic outlook or system of thought attaching prime importance to human rather than divine or supernatural matters; “a Renaissance cultural movement which turned away from medieval scholasticism and revived interest in ancient Greek and Roman thought”; and “(Among some contemporary writers) a system of thought criticized as being centred on the notion of the rational, autonomous self and ignoring the conditioned nature of the individual.”

But definitions in dictionaries and encyclopedias, though they are important, don’t tell us everything about how a word is used. What is interesting about the word ‘humanism’ is that it is used to mean such a variety of things, and to give a name to a particular spirit which is difficult to define but easy to recognise. Leaving out its use as a synonym for atheism, here are a few of the ways the term ‘humanism’ is used.

It is often used to mean something like ‘cosmopolitanism’. Humanists believe in the brotherhood (and sisterhood) of man, and that our affinity with the human race as a whole is more important than national or ethnic ties. (This doesn’t mean that national or ethnic ties aren’t important.)

In the field of psychology, ‘humanistic psychology’ is a departure from the rather bullish and anti-sentimental approach taken by Sigmund Freud and behaviourists such as B.F. Skinner (who wrote a book entitled Beyond Freedom and Dignity.) Humanistic psychologists tend to emphasise human freedom, creativity and the urge for wholeness, rather than seeing human beings as creatures at the mercy of their irrational impulses or social conditioning. They also tend to respect mankind’s spiritual aspirations.

In the field of literature, ‘liberal humanism’ is a school of criticism associated with F.R. Leavis and Matthew Arnold. They believed that literature speaks to something permanent and unchanging in human nature, and that the literary element in a book or poem is the most important thing about it. Anyone who has suffered through an English literature course in a modern university, with its obsession with feminist, post-modernist, post-colonial and

‘Deconstructionist’ theories—all of which are more interested in politics, and in the sex and colour and social class of the writer, than in the actual literary value of the work—will appreciate this school of thought.

Finally, humanism is generally considered to be an optimistic outlook. Humanists have faith in the ability of humans to rationally overcome social problems, faith in the intrinsic goodness of humanity, and faith in the ability of the human mind to comprehend reality.

If this is a fair description of the range of attitudes that belong under the term ‘humanism’, then I believe that humanism goes better—much, much better—with a Christian view of the world than it does with the philosophy of the atheist and the scientific materialist.

Why is that? I will defend my claim, but first I want to indulge in a personal digression.

To Boldly Go…

Why do I even care about humanism? I hope the reader will not guffaw if I admit that the TV show Star Trek: The Next Generation has a lot to do with it. (Bear with me, please!)

Star Trek: The Next Generation is, as its name implies, the second series of the Star Trek franchise, set some years after the adventures of Captain Kirk, Doctor Spock and Scotty. Like the first series, it follows the crew of the Starship Enterprise as they explore the galaxy, and come into contact with a bewildering variety of life forms and civilisations.

Star Trek is notable for its high moral tone. There are no anti-heroes amongst its cast. The crew of the Starship Enterprise are portrayed as being very principled and idealistic. The conflicts they encounter are more often solved by reason, and by coming to a better understanding with their antagonists, than by violence. Off duty, they perform Shakespeare plays, attend poetry recitals, and pursue other worthy cultural pursuits.

Although human civilisation in Star Trek has reached a point where all material needs have been met (you can get any meal you want by just ordering it from a ‘replicator’) the show repeatedly makes the point that man does not live by technology alone. One character—the super-intelligent android Data—yearns to become more like his human colleagues, and is intrigued by human concepts such as love, humour, and imagination.

I actually believe that Star Trek played a part in forming my own Christian worldview. (I was a teenager when The Next Generation was being first broadcast.) The universe it portrayed was not hostile and alienating, but rather filled with wonders and with intelligent life. Good triumphs over evil, love over conflict, time and again. The human spirit and the human mind are seen to be at home in the cosmos. It is hard to escape the conclusion that, despite Roddenberry’s intentions, there is a loving Providence behind the Star Trek universe—and that this Providence takes a special interest in human beings.

In short, Star Trek played no small part in making me a humanist, a Christian, and a Christian humanist.

Why Christians are Humanists

And now, to return to the question I left dangling above—why do I believe that Christians have more of a right than atheists to call themselves humanists?

I believe this because, from an atheist or materialist point of view, there is really nothing special about human beings. We are simply the by-product of immutable, impersonal natural forces—just like a wave or a flame. There is no reason to believe that the human mind should enjoy a privileged insight into reality. (Indeed, historians of science have pointed out that modern science arose in a Christian context, as a result of the Christian faith that God’s universe was comprehensible.)

Humanists who are atheists, or scientific materialists, have no reason—other than pure sentimentality—to think that human nature is basically good. If we are entirely the products of evolution, of ‘nature red in tooth and claw’, why would it be? Christians, on the other hand—for all our belief in sin, and the Fall—have faith that we were created in the image and likeness of God, and that “everything created by God is good” (1 Timothy 4:4).

Christians—and especially Catholics—actually proclaim the dignity of man in a way that secular culture has never succeeded in doing. Christianity, as a universalist religion, has always rejected racist ideologies that portray some people as sub-human. Its missionaries have respected, and indeed nurtured, the native cultures they encountered. As well as this, Catholicism defends human life from the moment of conception to the moment of natural death, on the basis of the dignity of the person. (Secular humanism can’t even give us a useful definition of a human being!)

Catholic social teaching defends the dignity of the human person (and the dignity of the family) against untrammelled market forces on one hand, and the unrestricted power of the State on the other. Catholicism embraces a humanistic holism, promoting— to quote the magnificent words of Pope Paul VI—“the good of every man, and of the whole man”. Finally, Pope Benedict XVI, and the Church’s Magisterium, has often warned of the dangers of technology in a manner similar to that of Neil Postman.

Meanwhile, the materialistic philosophies of modernity have brought us ever closer to the bleak prediction of philosopher Michel Foucault, who—in 1966—foresaw the possibility that “man would be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.”

So who, I ask, are the true humanists?

Saturday, April 24, 2021

The Year of Time and Space

Yesterday, I decided that this year-- the year from St. George's Day 2021 to St. George's Day 2022-- would be the Year of Time and Space for me.

I have a difficult and complicated relationship with time and space. I'm never quite sure where I am or what day it is. I have to think about it. I'm always impressed that most people can say "Good morning" or "Good afternoon" without even having to think about it.

Added to this, my sense of direction is abysmal-- truly absymal. When I try to convey to people just how bad my sense of direction really is, they invariably think I'm exaggerating. I can get lost almost anywhere.

I have a very limited understanding of spatial relationships. For instance, the library where I work has four floors. I find it extremely challenging to work out how the layout of one floor relates to the layout of the other floors, to know what's above my head or beneath my feet at any particular spot.

That's not all. I've lived in Dublin all my life, but my grasp of Dublin geography is worse than that of most people who have lived here for a year or two. Several times in my life I've been asked: "Are you really a Dubliner?".

And it's not just Dublin geography. I struggle with all geography. I can remember, in primary school, how the teacher used to pull down a large laminated map of Ireland and get us to memorize counties and rivers from it. This seemed utterly impossible to me and I couldn't understand how the other children could do it.

I wish I'd kept diaries all my life. I kept a continuous diary from June 2015 to some time in 2020. Then I gave up on it, but more recently I've been keeping a simpler chronicle, in a small desk diary. (My previous diary became so elaborate, so comprehensive, it was becoming a burden to keep it up.)

Despite grappling so clumsily with them, I'm completely fascinated by the concepts of time and space. This fascination has grown on me over the years.

I've always loved stories about travellers going to places which have a distinctive character of their own; the Odyssey (filtered through pop culture like Ulysses 31), Lord of the Rings, Star Trek, Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, and so on.

A lot of my conservatism has been a craving for special times and special places, a hunger for festival and tradition, for local and national character.

I think that's very legitimate, but I also think I miss out a lot on the more subtle differences in time and space. I've sadly been oblivious to many of them, through a lack of observational skills, and a tendency to absent-mindedness.

On a more abstract level, the very existence of time and space-- of different times and spaces-- has a kind of thrill for me.

I used to be a big soccer fan. Every soccer fan knows that Anfield, the home of LIverpool Football Club, has a famous sign in the players' tunnel which proclaims: "This is Anfield". The thought of that sign has always given me a thrill.

I get a similar thrill from the line that I've put in bold from Sir Thomas Wyatt's poem "Mine Own John Poins":

Nor I am not where Christ is given in preyFor money, poison, and treason at Rome—

A common practice used night and day:

But here I am in Kent and Christendom

Among the Muses where I read and rhyme;

Where if thou list, my Poinz, for to come,

Thou shalt be judge how I do spend my time.

Wednesday, April 21, 2021

Watching the Late Late Show

Yesterday, I was watching some old episodes and clips of the Late Late Show on YouTube. I mean, of course, from the time that Gay Byrne presented it. It was quite the nostalgia kick.

I'm at the age for nostalgia, undoubtedly. Admittedly, I've always been a nostalgist, but the call of the past seems especially compelling in one's forties. All of my siblings seem to be going through this right now (we are all aged between forty and sixty-- my younger brother just turned forty last week). They're all immersed in genealogical research, though I tend to be more drawn to oral traditions and collective memories.

Mortality has been much on my mind this week. I discovered that a friend of mine died last month. I call him a friend, but we hadn't been in touch for a few years. He was an elderly gentleman, somewhat cranky and argumentative, but I appreciated his flair for self-dramatization and the stories he would tell about his past. I knew he was lonely at the end but I hadn't seen him in a few years, so I feel guilty about that. I finally sent him an email a few weeks ago, not realizing it was already too late. Only when he didn't reply did I scan for obituaries.

Watching the Late Late Show certainly reinforced this sense of omnipresent mortality, of the world of my youth slipping over the horizon. One of the clips I watched was Gay Byrne interviewing Jack Charlton, the manager of the Irish international soccer team from 1985 to 1996. Both have died recently, Gay Byrne in 2019 and Jack Charlton in 2020. And, of course, my father also died in 2019. He was a huge admirer of Jack Charlton (though not of Gay Byrne).

I think about nostalgia a lot. Whenever anyone waxes lyrical about the days of their youth, or about some vanished era, the cynics are wont to say: "That's just nostalgia". But why use the word just there? Nostalgia is fascinating in itself. I can easily imagine a world without it, a world in which our vision of the past would be as clear-eyed and passionless as security camera footage. The strangest thing about nostalgia is its existence.

I like the fact that the human mind is not a passive receptacle of memory, that it does something with it. I've spent a lot of time wondering why we get nostalgic. There could be all sorts of reasons, of course; the most obvious being that the past really is better than the present, often enough.

But would that even be enough for nostalgia? After all, it's not simply a comparison of better to worse, which would hardly be much in itself. It's a particular atmosphere, a particular mood. Music is often be described as "nostalgic", even when there is no lyrics. For instance, Ralph Vaughan Williams's "Fantasia on Greensleeves" sounds nostalgic, even though there are no words.

One reason I think we feel nostalgia is because we suddenly see the past, or a particular period, as complete in itself, as possessing a certain wholeness. Anarchy is replaced by a pattern. Cacophony becomes music. It's somewhat akin, I imagine, to the reaction astronouts report when they look back at the earth and suddenly see it as one shining blue pebble in the darkness of space.

I know the nineteen-eighties was not really a good time in Ireland. All anyone ever seemed to talk about was emigration, unemployment, the Troubles in Northern Ireland, drugs, and so forth.

But, in a strange way, I feel "at home" in that period of Irish history more than any other. It was a time when just having a job was seen as a good thing, an achievement. Everybody was poor (or so it seems to me, looking back) so there was more solidarity, and less careerism and consumerism.

Catholicism, too, remained omnipresent in Irish society, even though the iceberg of the sex scandals was floating towards us. In the Jack Charlton interview, he describes the Irish team meeting the Pope during the World Cup finals in Italy in 1990. That story has often been told, but more interesting was his statement that he regularly arranged Mass for the team on away games. I wonder if that still happens?

One of the episodes I watched was a tribute to Paul McGrath, the legendary defender who was the foundation of Charlton's Irish team. It was a This Is Your Life type of episode, with various friends of the great man giving their memories of him. Among these was one man, someone who had worked as a security guard with McGrath in his younger days, who was now a Catholic priest. He was a reasonably young fellow, too. (He describes McGrath as "coloured" at one point, a poignant reminder of the pre-political correctness days. Nobody bats an eyelid.)

The Catholicism of eighties Ireland, as I've said elsewhere, was mellow and self-confident in a way that no longer seems possible. Certainly, this mellowness and self-confidence could just as well be called inertia and complacency. And it was, to some extent. But not entirely. It was simply accepted (for the most part) that religion was a feature of Irish life, and a good thing-- that the Catholic Church was a pillar of teh nation.

The Late Late Show was (and still is) broadcast on Friday night, when school was as far away as it would ever be, outside the holidays. I remember falling asleep, week after week, with "Uncle Gaybo's" velvety tones washing over me. Actually, I didn't like Uncle Gaybo much at the time, perhaps because my father didn't like him much. But my mother adored him, as did middle-aged and elderly women all over Ireland. He had the boyish good looks and gentle, smooth manner that seemed to appeal to older Irish women at that time.

More than anything else, in retrospect, The Late Late Show seemed like a kind of fireplace of the Irish nation, where it gathered once a week. It made the nation seem like one big extended family. This has always been my favourite conception of nationality. "The nation is the family writ large", as Patrick Pearse said.

I've often wondered what it must feel like to come from a "great nation"-- great in the sense of big. I've only ever known the cosiness of a small nation. I wouldn't trade it for greatness.

I could write much more about The Late Late Show, but perhaps that's enough for now.