I was thinking especially of one my favourite poems of all time, the blank verse "Ulysses", which I believe will be remembered long after James Joyce's novel has become a period piece and a curiosity.

What amazes me about this poem is how such simple language and simple thought manages to be so unforgettable. And it IS unforgettable, since it's constantly quoted and alluded to. Take these lines, for instance:

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when

Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour'd of them all;

And drunk delight of battle with my peers,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy.

I am a part of all that I have met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro'

Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

There are no great fireworks of linguistic virtuosity here. The language is about as simple and plain as it could get. There are hardly any similes or metaphors and those that are there are very commonplace, other than the great symbol of the arch. There is nothing in this passage that might not have been said by anybody. And yet it's one of the greatest flights of poetry in the English language. It defies analysis. I've especially always found the line: "Manners, climates, councils, governments" to be electrifying. But it's just a string of nouns! (The same could be said of Milton's "Thrones, dominations, princedoms, virtues, powers," or-- a less famous example-- "WIne and oil and honey and milk" from "The Wanderings of Oisin" by Yeats.)

Don't get me wrong. I love Quentin Tarantino. I love horror films, which often feature violence. I have no problem with violence in stories per se. I'm not talking about graphic violence here, just violence as a plot device.

It just seems like a failure of human imagination. Is life so boring to us, as a species, that most of our stories have to involve the destruction or threatened destruction of human life?

This is why I have such a high regard for situation comedies, which are generally about ordinary life-- the broad sweep of daily life with its routines and variety. I would like to think that ordinary life is worth living, and worth celebrating. That it's not only the extremes of life that are interesting.

This is why Groundhog Day is my favourite film. It has a supernatural plot but it's all about the beauty of ordinary life.

For a long time I've been a ferocious critic of political correctness. I imagine people who see me in the street think: "There goes Maolsheachlann Ó Ceallaigh, the ferocious critic of political correctness." However, more recently I've been troubled by a kind of contradiction in my own Thought.

This is it: I tend to believe that taboo, reverence, and piety are good things in themselves. Don't get me wrong, I wish all those things were directed towards their proper objects, but even IN THEMSELVES they seem admirable to me.

And all those things are abundantly present in political correctness. People who trip themselves up constantly trying to use the correct epithets are, in a sense, showing a sort of piety, a sort of reverence. It's misdirected but it's real. And I don't have the slightest problem against censorship on the grounds of public morals; I think Mary Whitehouse was a hero. But isn't this just what the PC brigade are pushing for, according to their own lights?

My gorge still rises at political correctness, don't get me wrong. And I still consider it a mortal enemy. But there is a little part of my mind that asks: "Are you being completely consistent here? Shouldn't you acknowledge a healthy impulse even in your enemy, "to honour as you strike him down' "? Perhaps Nietzsche was onto something when he said "you may have enemies you hate, but not enemies you despise."

(I would like to think this is the most pompous Facebook post ever.)

For a long time I've pondered the problem of clichés. It seems unreasonable that a happy turn of phrase should become shopworn after a certain amount of time. Why should proverbs be cherished when "clichés" are scorned? I love turns of phrase like "a walk down memory lane" or "in the cold light of day" and see no reason why they shouldn't be used again and again. I see no reason why language should be constantly mown like a lawn.

I was listening to someone talking the other day and she used such a phrase--I forgot what-- but I noticed how listlessly she used it. She drawled it out. Perhaps that's the difference? Perhaps clichés become lifeless because we use them lifelessly, or apologetically, or half-heartedly? Perhaps "clichés" remain fresh if we use them with as much relish as they were used when they were coined?

There are other features, although I hadn't thought of them. I guess restaurants, saunas, indoor soccer courts, plazas, that kind of thing.

I don't know if such a place is even possible. I did read that spiral escalators are real. Mitsubishi are the only company that make them.

Do other people daydream about imaginary places? I do this quite a lot.

Here's an interesting thing. Grafton Street is Dublin city centre's "showcase" street and it's pedestrianized. A few weeks ago I was taken aback when I realized the paving stones on Grafton Street are grey, rather than the pinky-red I'd always seen in my mind. In fact, they have been grey since 2015. But I've mentioned this to a couple of other people (both Dubliners) and they both said: "What, they're not red? I thought they were." As Sherlock Holmes would say, we see but we do not observe. Certainly I don't! But I'm even more surprised when it's others, too.

|

I watched all the series of the "reimagined" Battlestar Galactica a few years ago, back to back. On the whole I found it poor. It was the anti-Star Trek and I much prefer Star Trek's idealism to Battlestar's cynicism. But some scenes have really stuck in my memory. Spoilers ahead...

First off, the sequence at the very beginning when the Cylons are attacking Galactica, wave after wave, relentlessly, and the Viper pilots are at breaking point trying to ward them off incessantly. This often comes into my mind when I feel overwhelmed.

Then there was the episode where Baltar was vindicated for cooperating with the Cylons under the occupation, since resisting would have caused much more loss of life. I'm generally on the pragmatic side of such questions, rather than the "liberty or death" side.

The scene where they discover Kolob is a post-atomic wasteland. Gut-wrenching.

And having some Luddite tendencies I loved the way

it ended, when they decided to discard all their technology.

I thought the original BSG was the business as a kid. I watched it again recently and realized it was dire! Even if Dirk Benedict is always awesome.

Here's something odd. I've mentioned before my terrible sense of geography, all geography-- world, European, Ireland, Dublin, my own immediate environment.

But allied to this is a deep fascination with the

concept of place which occasionally makes me want to get a better grasp. Not

just place, but time. Those two things never cease to fascinate me. In

particular, special times and places, and liminal times and places. The word

"lobby" gives me endless delight.

We have to keep a log of all the questions we get asked in the library. There are different categories. Two are "Directional-- library" and "Directional-- campus". So if somebody asks about something that's JUST outside the library, literally a few paces (for instance, the Access and Life-Long Learning centre, in the same building) it's "Directional-- campus" instead of "Directional-- library". And every time I do this I feel a delicious frisson at that distinction.

You wouldn't be up to me.

What put this in my head are the last lines of Foundation and Earth by Isaac Asimov, which I must have read more than thirty years ago, but which have stuck in my mind all that time:

' "After all", and here Trevize felt a sudden twinge of trouble, which he forced himself to disregard, "it is not as though we had the enemy already here and among us."

And he did not look down to meet the brooding eyes of Fallom--hermaphroditic, transductive, different--as they rested, unfathomably, on him.'

It came into my mind just now as I was thinking of

the preservation of the public and the private. There have been times in

history when the public swallowed up the private.

Totalitarianism, for instance. Or you even see it today with people for whom EVERYTHING is political and who can't understand that some things should be kept free from politics. But, on the whole, I think our time is one where the private has swallowed up the public. People lives their lives with little sense of a greater whole-- I don't mean in a political sense (there is that, as the lockdowns showed, however ill-advised they were) but in a cultural, spiritual sense.

We also live in a time when the universal is threatening to swallow up the particular-- as though we didn't need both.

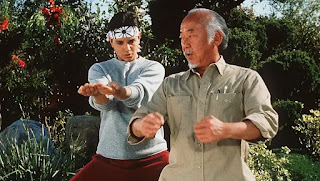

I always love it when someone says something like: "I learned my logic in a hard school", or "I was always taught to break things down into their simplest elements", or anything that harkens back to their training, formation, induction, etc. It can be anything; someone talking about a knack their parents showed them in the kitchen, or a professor saying, "As my old professor always used say..." I suppose at that moment I get an image of skills and habits and traditions being handed down from person to person, down a long tunnel of time. Or maybe it shows the human side to the academic, or the technical, or the professional, or whatever type the skill is. Or maybe it's that you realise that, even in something very demanding and precise, there is still room for personality and rapport. Well, I suppose it's all these things.

This is why I love movies and books about pupil-mentor relationships like The Karate Kid or Dead Poets' Society.

No comments:

Post a Comment