Here's another gem (or so I'd like to think) from my archives. This is a book review I had published in the library newsletter, some years ago. It's rather appropriate to the post about books that I put up yesterday.

First, a quick glossary. "IRM" is Information Resource Management, the department of our library that deals with the acquisition and cataloguing of books. (Or rather, that is its former name. Happily, it is now called "Collections" instead.) "RFID" is a form of electronic book tagging which lets books be borrowed and returned using radio frequency. It was a new thing in the library at the time.

The reference to telegraph pole insulators is extra amusing in hindsight, since my current office mate actually collects them, and gave me one for my birthday a few years ago. I didn't know that at the time. I'm not even sure he was working in the library back then.

Nobody in the library even mentioned this article to me. Pearls before swine. (That's a joke.) Maybe my blog readers will be more interested.

I’m

sure it’s happened to everyone who works in a library, at some time or other.

You’re working your way through a trolleyload of books. Maybe your mind isn’t a

hundred per cent on what you’re doing. You pick up a volume. You glance at the

title. Your eyes widen. You flick through the pages, growing more and more

incredulous. Two minutes later, you’re calling to a colleague; “Come here,

you’ve got to see this”. Two more minutes later, you’ve decided that, no

matter how weird or obsure the subject, no matter how far-fetched the theory, somebody

somewhere has written a book about it.

Well,

guess what—somebody has written a book about that, too, and we have it in our

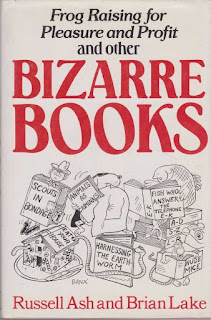

shelves. Bizarre Books by Russell Ash and Brian Lake, published in 1985,

is a celebration of the fact that nobody needs a license (or even an iota of

good sense) to publish.

Double

entendre titles, ridiculous author’s names, far-out subjects, nutty

theories…it’s all here, and as respectably-sourced as anyone could ask for.

You

know those children’s jokes where a book title is paired with a humorously

appropriate author’s name? Well, according to Bizarre Books, truth

really is stranger than fiction. There really is a book called Punishment by

Robin Banks (Penguin, 1972) and another called The Art of Editing by

Floyd K. Baskette and Jack Z. Sissors. There is also a Motorcycling for

Beginners by Geoff Carless. But my favourite in the apt author’s name

category has to be Fuel Oil Viscosity-Temperature Diagram by Guysbert B.

Vroom (1926).

Then

is the J.R. Hartley Award for most obscure book subject. In 1897, the National

Temperance League found the money to publish Octogenarian Teetotalers, with

One Hundred and Thirteen Portraits. It is, as the authors of Bizarre

Books put it, “probably the only illustrated directory of geriatric

abstainers ever published”. (They even reproduce an illustrated double-spread

from this unjustly forgotten work.)

We

also get a picture from Philippe Halsman’s Jump Book, a collection of

photographs showing various celebrated people…jumping. The picture reproduced

shows the Duke and Duchess of Windsor leaping in the air, shoeless and

hand-in-hand, obviously fully recovered from the Abdication Crisis. Apparently

Bertrand Russell refused to jump—but plenty of other notables (including

Salvator Dali) seem to have asked, “How high?”.

There

are other mind-bogglingly specific books—Fifty New Creative Poodle Grooming

Styles and The Influence of Mountains Upon the Development of Human

Intelligence deserve honourable mention. But let us move on to

eyebrow-raising titles. I Was a Kamikaze (1973) definitely begs the

question. Jokes Cracked by Lord Aberdeen (1929) shows a rather

funereal-looking old Scotsman on the cover, and I’m sure many people in IRM

will be keen to learn The Joy of Cataloguing (1981).

(Perhaps

I should mention here that we have a few crackers in our own stock. One of my

favourites is Modern Thinkers on Welfare by George and Page. I was one

of those myself for several months after leaving college.)

But,

just as they say there’s someone out there for everyone, there’s obviously a

reader for every book. As the introduction to Bizarre Books puts it:

“But what is odd? It is quite clear that one person’s bizarre book is another’s

bread and butter. We thought Searching for Railway Telegraph Insulators a

hugely funny and esoteric title until a lecturer in electronics asked where he

could get a copy of this key text.”

Now,

if you excuse me, I have to get back to work on my own magnum opus on the life

of the contemporary library assistant, Me and RFID…