You think you can escape social media by not having a social media account? Oh, you poor fool!

Here's a selection of my recent Facebook posts, which I think everybody should have to read. One of them is a meditation on Shakespeare's "All the world's a stage" speech that was meant to be the second part of a two-part post some time ago. I never got around to writing it.

A book I was reading got me thinking about Catholicism and other denominations of Christianity.

I grew up in a Catholic family and country and, in all honesty, Catholicism seemed the most rational religion to me even when I was an agnostic. At a certain point of my life I found it impossible to continue as an agnostic and I spent a lot of time investigating religion. I never really took seriously the claims of other faiths to be THE true faith, mostly because of the apostolic succession and the length and breadth of Catholic history, as well as the clarity and confidence of its dogmas.

Here's the thing though; I never really had a taste for Catholic chauvinism or triumphalism. Maybe it's because growing up in Ireland meant Catholicism wasn't in any way exotic or glamorous. But also because I never doubted for a second that there was good in other denominations. It seems blindingly obvious to me that there is holiness to be seen in many Christian denominations. It even seems that God has showered particular gifts on other denominations that he hasn't, to the same degree, on Catholicism. Although I don't doubt heresy and apostasy is always a bad thing, I get the feeling God can work good from evil and bring out "the unsearchable riches of Christ" in a different way in other denominations.

I don't know theologically accurate that is and I'm always open to correction.

Next time someone being introduced to me says: "I'm a hugger", I think I'll reply: "Really? I'm a puncher."(Just joking. But that's one thing I don't miss from before Covid...)

I've often heard that nobody is interested in other people's dreams. I'm interested in them. I've also heard it said that a bore is someone with a very specific interest who can't help talking about it. I like hearing about obscure interests, too.

What I don't like is "I was proved right" stories. But lots of people delight in telling these. It's funny how nobody talks about the predictions they made that went awry, or the arguments they lost.

I am possibly just jealous because I've never been right about anything, but I don't think that's it entirely.

Isn't it interesting that, in England, the Catholic past is remembered (by some) as "Merrie England", while in Ireland there is no such nostalgia? Many of us are nostalgic for Catholic Ireland, but not for "Merrie Ireland"...

For some years now, I have a practice whereby I memorize poems (and hymns, nursery rhymes etc.) and recite them to myself, every now and again, to keep them fresh. There's 136 on the list right now. It's been on "maintenance" mode for a while, ever since I've been trying to master basic geography.

Anyway, it includes Shakespeare's "All the world's a stage" speech. I'm not the biggest Shakespearean and, honestly, I'm not sure why I picked it as I never particularly liked it. But saying it to myself over and over has given me a deeper appreciation, as with many of the pieces.

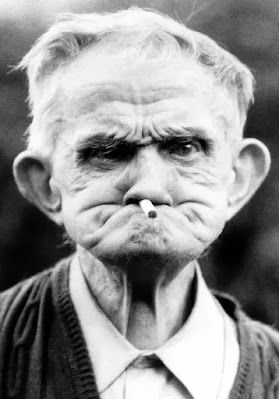

The obvious first impression of the speech is how undignified and ridiculous it makes mankind seem, as to be expected given the melancholy speaker. At every stage in life man is making a fool of himself, whether over love or honour or self-importance or simple decrepitude.

Even if you were never a soldier, you were probably an obnoxiously opinionated twenty-something putting the world to rights, perhaps a crusader for some cause. Even if you were never a "justice" (judge?), we all reach the pinnacle of whatever authority or standing we have, dispensing wisdom and verdicts. And then we are still as silly as the lovelorn teenager.

But, when I speak the speech to myself, I feel a second reaction, as well as this sense of the absurd-- a sort of tenderness and relief. Yes, we are like this. We are all like this, and none of us are that much better or worse. It's not so bad. Our creatureliness is very endearing, when you look at it from outside. I actually feel a huge weight lift off me when I recite this speech to myself-- the same sort of relief C.S. Lewis described as letting go of the burden of pride. I've been terrified of being ridiculous all my life, and this speech says: "Relax. You ARE ridiculous. So is everybody else."

And it makes me think of my father. I saw him go through all the later stages and heard him describe the earlier ones. I saw him "sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything". And he remained himself. Underneath all the indignity there is a deeper dignity.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms;

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

It's so tiresome that in the Irish media today, the issue is never the issue and there's always some ulterior message to the one being transmitted.

For example, two articles I read in the Irish Times today. One was an article congratulating the Irish government on standing up for sovereignty and neutrality, in the diplomatic sparring with Russia. As though the Irish Times or any of the Irish media have anything but contempt for national sovereignty and neutrality. They have been undermining both for decades. In this instance they are just slogans to be used as the West's globalist ambitions press eastward.

Another was an article complaining about Spotify and how it denies musicians their right to be paid. Maybe the Irish Times DOES care about this-- at some level-- but who could believe that this is really anything but outrage at Spotify playing host to Joe Rogan, who questions their orthodoxies?

It's nauseating.

One of the reasons I am such a defender of the particular is because I feel the particular elevates the universal. I am currently re-reading the Oxford Book of Friendship. It is very interesting, and pleasing, to see how the concept of friendship has been celebrated and discussed through so many ages, in so many cultures; the book contains excerpts from the ancient world right up to the modern age, and across cultures.

The stronger the particular is, the stronger is the universal. Think how much it says of Shakespeare that he is translated into so many languages and loved by so many different peoples. But imagine we had the monoculture many people seem to want, one worldwide culture with one language. What would be special about universality then? Everything would be universal, and there would be no distinction or thrill to it. People talk about eliminating boundaries and barriers as if it is the most exciting thing in the world; but when they are gone, you lose all the excitement of ever transcending them again.

I continue to believe church attendance rates matter. Cultural Christianity matters. It has a knock-on effect on other things, like religious freedom and public policy.I'm baffled and dismayed by Christians who seem to be indifferent to it, who seem to think it would be better to have a tiny "remnant" of orthodox Christians-- and it's always THEIR interpretation of orthodoxy, or their favourite YouTuber's interpretation of orthodoxy-- rather than accept any perceived or real imperfections. Who write off vast swathes of professing Christians as "not really Christian, anyway".

There is of course the opposite extreme-- a preoccupation with Christianity as a social force, with the will-o-the-wisp of reviving Christendom. (I've met this entirely among Catholics myself, but it may have its variant in other denominations.) Surprisingly, I've noticed that both views can actually co-exist in the same person.

Am I wrong? I might be wrong. This is my view.

Surely it is always better than someone has a relationship with Christ than not?

It's funny that early morning is probably the most solid, public, tangible part of the day-- everyone going to work, the morning headlines, cleaners doing their stuff, the mind generally at its freshest and brightest, the "broad light of day" illuminating everything-- but only a few hours ago everybody was hallucinating, lost in private dreamworlds.

My favourite U.S. state name is "Vermont". I don't know why I like it so much.It sounds like "Vermouth". I don't know if I've ever had a vermouth but I like the scene in Groundhog Day where Rita asks for: "Sweet vermouth on the rocks with a twist, please". Well, several scenes.

It makes me think of Fry's Chocolate Cream, a chocolate bar which has a kind of minty fondant centre. Maybe because "mont" sounds like "mint, although that doesn't adequately explain the association.

Also, the song title "Moonlight in Vermont" gives it romantic associations.