There are no great fireworks of linguistic virtuosity here. The language is about as simple and plain as it could get. There are hardly any similes or metaphors and those that are there are very commonplace, other than the great symbol of the arch. There is nothing in this passage that might not have been said by anybody. And yet it's one of the greatest flights of poetry in the English language. It defies analysis. I've especially always found the line: "Manners, climates, councils, governments" to be electrifying. But it's just a string of nouns! (The same could be said of Milton's "Thrones, dominations, princedoms, virtues, powers," or-- a less famous example-- "WIne and oil and honey and milk" from "The Wanderings of Oisin" by Yeats.)

I was looking through a catalogue of movies and I was depressed at how

many centre on violence. I think it's fair to say that most films have violence

or crime as central themes.

Don't get me wrong. I love Quentin Tarantino. I love horror films, which

often feature violence. I have no problem with violence in stories per se. I'm

not talking about graphic violence here, just violence as a plot device.

It just seems like a failure of human imagination. Is life so boring to

us, as a species, that most of our stories have to involve the destruction or

threatened destruction of human life?

This is why I have such a high regard for situation comedies, which are

generally about ordinary life-- the broad sweep of daily life with its routines

and variety. I would like to think that ordinary life is worth living, and

worth celebrating. That it's not only the extremes of life that are

interesting.

This is why Groundhog Day is my favourite film. It has a supernatural

plot but it's all about the beauty of ordinary life.

For a long time I've been a ferocious critic of

political correctness. I imagine people who see me in the street think:

"There goes Maolsheachlann Ó Ceallaigh, the ferocious critic of political

correctness." However, more recently I've been troubled by a kind of

contradiction in my own Thought.

This is it: I tend to believe that taboo,

reverence, and piety are good things in themselves. Don't get me wrong, I wish

all those things were directed towards their proper objects, but even IN

THEMSELVES they seem admirable to me.

And all those things are abundantly present in

political correctness. People who trip themselves up constantly trying to use

the correct epithets are, in a sense, showing a sort of piety, a sort of

reverence. It's misdirected but it's real. And I don't have the slightest

problem against censorship on the grounds of public morals; I think Mary

Whitehouse was a hero. But isn't this just what the PC brigade are pushing for,

according to their own lights?

My gorge still rises at political correctness,

don't get me wrong. And I still consider it a mortal enemy. But there is a

little part of my mind that asks: "Are you being completely consistent

here? Shouldn't you acknowledge a healthy impulse even in your enemy, "to

honour as you strike him down' "? Perhaps Nietzsche was onto something

when he said "you may have enemies you hate, but not enemies you

despise."

(I would like to think this is the most pompous

Facebook post ever.)

For a long time I've pondered the problem of

clichés. It seems unreasonable that a happy turn of phrase should become

shopworn after a certain amount of time. Why should proverbs be cherished when

"clichés" are scorned? I love turns of phrase like "a walk down

memory lane" or "in the cold light of day" and see no reason why

they shouldn't be used again and again. I see no reason why language should be

constantly mown like a lawn.

I was listening to someone talking the other day

and she used such a phrase--I forgot what-- but I noticed how listlessly she

used it. She drawled it out. Perhaps that's the difference? Perhaps clichés

become lifeless because we use them lifelessly, or apologetically, or

half-heartedly? Perhaps "clichés" remain fresh if we use them with as

much relish as they were used when they were coined?

I like to fantasize about imaginary places.

Recently I've been daydreaming about a gigantic indoor space, made mostly of

glass, with winding spiral escalators taking people up and down. This space has

many swimming pools layered one on top of the other, each one glass-bottomed,

the water a delicious blue green. There are also powerful fountains on each

level. The air is full of echoes, voices and splashes.

There are other features, although I hadn't thought

of them. I guess restaurants, saunas, indoor soccer courts, plazas, that kind

of thing.

I don't know if such a place is even possible. I

did read that spiral escalators are real. Mitsubishi are the only company that

make them.

Do other people daydream about imaginary places? I

do this quite a lot.

Here's an interesting thing. Grafton Street is Dublin city

centre's "showcase" street and it's pedestrianized. A few weeks ago I

was taken aback when I realized the paving stones on Grafton Street are grey,

rather than the pinky-red I'd always seen in my mind. In fact, they have been

grey since 2015. But I've mentioned this to a couple of other people (both

Dubliners) and they both said: "What, they're not red? I thought they

were." As Sherlock Holmes would say, we see but we do not observe.

Certainly I don't! But I'm even more surprised when it's others, too.

I watched all the series of the

"reimagined" Battlestar Galactica a few years ago, back to back. On

the whole I found it poor. It was the anti-Star Trek and I much prefer Star

Trek's idealism to Battlestar's cynicism. But some scenes have really stuck in

my memory. Spoilers ahead...

First off, the sequence at the very beginning when

the Cylons are attacking Galactica, wave after wave, relentlessly, and the

Viper pilots are at breaking point trying to ward them off incessantly. This

often comes into my mind when I feel overwhelmed.

Then there was the episode where Baltar was

vindicated for cooperating with the Cylons under the occupation, since

resisting would have caused much more loss of life. I'm generally on the

pragmatic side of such questions, rather than the "liberty or death"

side.

The scene where they discover Kolob is a

post-atomic wasteland. Gut-wrenching.

And having some Luddite tendencies I loved the way

it ended, when they decided to discard all their technology.

I thought the original BSG was the business as a

kid. I watched it again recently and realized it was dire! Even if Dirk

Benedict is always awesome.

Recently I watched a deacon bowing before a priest, who

blessed him before he read the Gospel passage. I thought of what a beautiful

gesture of humility it was, and how sad it is that egalitarianism is so often

pitted against hierarchy. I do believe in egalitarianism, in several senses--

most importantly, that I don't think anybody is of inherently less dignity than

anybody else. And I generally prefer everything that pertains to the common

herd as opposed to elites of any kind-- cuturally and socially. But how can we

do without hierarchy, not just as a necessary evil but as an opportunity for

humility, reverence, chivalry etc? Why should we let a silly resentment take

away the beauty of a layman kissing a bishop's ring, a commoner using a special

form of address for an aristocrat, men showing chivalrous courtesies to women,

the young respecting the old, etc? It's not about inferiority or superiority at

all, and it seems to me that such ceremonial forms are a kind of 'brake'

against seeing life in those terms. Once you see everything in terms of power

or a competitive pecking order, you are using the logic of Hell-- whether that

is understood in religious or secular terms.

Here's something odd. I've mentioned before my

terrible sense of geography, all geography-- world, European, Ireland, Dublin,

my own immediate environment.

But allied to this is a deep fascination with the

concept of place which occasionally makes me want to get a better grasp. Not

just place, but time. Those two things never cease to fascinate me. In

particular, special times and places, and liminal times and places. The word

"lobby" gives me endless delight.

We have to keep a log of all the questions we get

asked in the library. There are different categories. Two are

"Directional-- library" and "Directional-- campus". So if

somebody asks about something that's JUST outside the library, literally a few

paces (for instance, the Access and Life-Long Learning centre, in the same

building) it's "Directional-- campus" instead of "Directional--

library". And every time I do this I feel a delicious frisson at that

distinction.

When I was about eleven, my class went to Ennis to

participate in the Slógadh, an Irish-language festival of culture. (We won our

category, incidentally-- we were an overperforming working-class school that

put massive practice into such things.) Anyway, I remember we were sitting in

the lobby (!) of a hotel past midnight, and I made a reference to tomorrow.

"It is tomorrow", another kid said. And that sentence gave me so much

delight I still remember it. Part of my mind sees time and space as this

chaotic jumble, and another part is constantly delighted and amazed that it's

not.

You wouldn't be up to me.

Do you have any examples of great final sentences/passages from books?

They don't have to be novels.

What put this in my head are the last lines of Foundation and Earth by

Isaac Asimov, which I must have read more than thirty years ago, but which have

stuck in my mind all that time:

' "After all", and here Trevize felt a sudden twinge of

trouble, which he forced himself to disregard, "it is not as though we had

the enemy already here and among us."

And he did not look down to meet the brooding eyes of

Fallom--hermaphroditic, transductive, different--as they rested, unfathomably,

on him.'

When I think of what I believe in, aside from the

obvious answer: "Catholicism", it often comes down to the concept,

"the preservation of differences."

It came into my mind just now as I was thinking of

the preservation of the public and the private. There have been times in

history when the public swallowed up the private.

Totalitarianism, for instance. Or you even see it

today with people for whom EVERYTHING is political and who can't understand

that some things should be kept free from politics. But, on the whole, I think

our time is one where the private has swallowed up the public. People lives

their lives with little sense of a greater whole-- I don't mean in a political

sense (there is that, as the lockdowns showed, however ill-advised they were)

but in a cultural, spiritual sense.

We also live in a time when the universal is

threatening to swallow up the particular-- as though we didn't need both.

There seems to be a constant battle to preserve the

different sides of man's existence. Discovery and tradition. Individuality and

community. Equality and the need for hierarchy. So many others. (Of course, some people are fighting a battle to collapse man's many-sidedness.)

I always love it when someone says something like:

"I learned my logic in a hard school", or "I was always taught

to break things down into their simplest elements", or anything that

harkens back to their training, formation, induction, etc. It can be anything;

someone talking about a knack their parents showed them in the kitchen, or a

professor saying, "As my old professor always used say..." I suppose

at that moment I get an image of skills and habits and traditions being handed

down from person to person, down a long tunnel of time. Or maybe it shows the

human side to the academic, or the technical, or the professional, or whatever

type the skill is. Or maybe it's that you realise that, even in something very

demanding and precise, there is still room for personality and rapport. Well, I

suppose it's all these things.

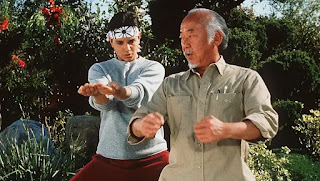

This is why I love movies and books about

pupil-mentor relationships like The Karate Kid or Dead Poets' Society.