I was once listening to an interview on RTE radio in which a foreign visitor described Ireland as a "toytown". She didn't mean it in a disparaging way. She felt a sort of surprise to see that Ireland was its own country, with its own flag and government buildings and so forth. (I can only vaguely remember the interview.)

I'm very familiar with this sensation. I have it all the time myself, although I'm a native of the country. It's a pleasing sensation.

Ireland is a small country, with only five million inhabitants (a big increase in my lifetime). Of course, there are many other countries with similar populations. But perhaps being sandwiched between Britain and the USA gives us (and others) a greater sense of our own smallness.

For my part, I'm glad that I live in a small country. I can't imagine wanting to live in a large country.

The fact that it took so long to achieve independence, and that this occurred almost within living memory, gives a certain added value to our political institutions. We know how much they cost, and how eagerly they were sought. Or, to put it less grandiosely, they was a lot of hype about them.

I still feel this strange sense of surprise all the time. Even though my father was born in an independent Ireland, the sight of an Irish flag flying still makes me do a bit of a mental double-take. "Well, look at that, we have our own country."

And living in a small country means the ordinary person has way more access to the central institutions of that country. I work in the university with the greatest number of students in the Republic of Ireland. But there are only a handful of Irish universities anyway. There's a very good chance that any given person I meet is a graduate of University College Dublin.

The college's academic staff includes many prominent figures in Irish life. Ireland's most prominent historian, Diarmaid Ferriter, is a regular visitor to the library.

When it comes to history, UCD has a long roll-call of famous Irish writers, politicians, and others who graduated from it.

The word "national" features around campus quite a lot. We have the National Folklore Collection, the National Hockey Stadium, and the National Virus Reference Laboratory-- the last of which featured very prominently in the news during the Covid pandemic, as you can imagine.

But it's not just UCD. Twice a day, on my way to work and on my way home from work, I walk past the main studios of RTÉ, Ireland's national broadcaster.

A lot of my conservative friends would love RTÉ to be abolished, or at least for the license fee that funds it to be abolished, seeing it as little more than a peddler of woke propaganda. I feel differently. While I don't deny the bias for a second-- who could?-- I have a lot more respect for institutions, especially old institutions. What would replace RTÉ? Well, non-Irish stations, for the most part. Besides, the license fee also funds Radio na Gaeltachta and TG4, the Irish language stations.

Similarly, I would not like to see The Irish Times or any other Irish newspaper go out of business. They are a part of Irish history.

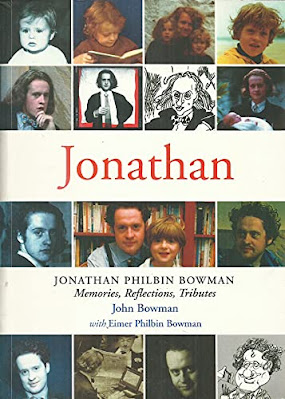

Recently, I've been reading a book called Jonathan, about the late journalist and broadcaster Jonathan Philbin Bowman, who died in the year 2000, at the tragically young age of thirty. He was a precocious kid, the son of a famous broadcaster, who appeared on national television in his teens to announce he was giving up school to go straight into journalism.

As with all precocious kids, I found him nothing but obnoxious when I was a kid myself. But I came across the book (a series of recollections by different people, compiled by his father, many of which are quite blunt about his shortcomings) on the book exchange outside the library, and found it surprisingly compelling.

I was interested in the book partly because I'm always interested in Dublin characters and literary figures. I like reading about Brendan Behan and Patrick Kavanagh and Myles Na Gopaleen and people like that.

But I was especially interested in Jonathan Philbin Bowman because he was such a free spirit, as evidenced by his decision to quite school in his teens. He was also the sort of person who would invite himself to dinners and give flowers to everybody he knew.

Free spirits are interesting to me because they seem to give a new life to their surroundings. It's fascinating that there's a limit to every free spirit; or at least, there's a background. William Blake was the most original figure imaginable, but he was still utterly English.

Even free spirits have a history, an accent, a tradition, a physical environment which they share with others. And somehow, seeing them in this context, we see the context itself anew-- as though for the first time. (David Thornley, the Labour MP and Catholic convert, is another Irish free spirit who interests me in the same way.)

I touched on ideas like these in my recent blogpost The Sky and the Ground.

I spoke earlier about the strange sense of surprise I feel whenever it occurs to me that Ireland is an independent state, a country of its own. But there's another and more general sensation of "surprise" that often hits me; surprise that the person in front of me exists in the same place and time as I do.

This seems absurd on the face of it. Everybody has to be alive at some time and some place, and there have to be other human beings who share our environment-- it's not like we could pop up out of the ground.

But I can't shake the feeling. Nor do I want to. The fact is that this person in front of me, in all their uniqueness-- "once only since the world began, never before and never again"-- exists here and now. Not in ancient Egypt or the Russian steppes or in the vast depths of prehistory, but here and now.

I know this sensation isn't unique to me, since I recently heard the Irish writer John Waters describe his own experience of it.

As a sort of sub-category of that, there is the "surprise" of sharing a nationality. Walking the same streets, having the same collective memories, using the same buses and trains, and so forth. And in the case of a small nation, this sense of "surprise" is all the more vivid. So I'm happy to live in toytown.

No comments:

Post a Comment