I love books. I've always loved books. I'm most definitely a bibliophile, although I'm not a connoiseur. I don't particularly get excited about first editions or the quality of bindings. In fact, being irremediably plebeian, I've always preferred paperbacks to hardbacks. They're more comfortable to hold in your hands.

I'm not a fast reader, and I'm not as well-read as I'd like to be. I wish I'd spent much, much more time reading when I was a kid. But books have always excited me in a unique way.

Whenever I find myself in a new house, I always drift towards the bookshelves, and wish I could spend more time just silently scanning them. I can rarely pass a bookshop without stopping in it.

I'm fascinated by all the aspects of a book-- the title, the dedication, the acknowledgements, the publisher's logo, the introduction, and so on.

One of the aspects that fascinates me is the opening. The curtain is pulled away and we see out the window onto-- what? It could be anything. The author addresses us for the first time, and we hear his or her unique voice, coming to us from some other time and place.

Of course, there are many famous opening lines. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times." "Call me Ishmael". "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there." "Gaul is divided into three parts." And let's not forget the much-mocked but inimitable "It was a dark and stormy night."

There are some not-so-famous openings that have stuck with me, too. For instance, these opening lines from Clive Baker's dark fantasy novel Weaveworld (a thumping great book that I never actually finished), which I think are worth quoting at some length:

Nothing ever begins.

There is no first moment; no single word or place from which this or any other story springs.

The threads can always be traced back to some earlier tale, and to the tales that preceded that: though as the narrator’s voice recedes the connections will seem to grow more tenuous, for each age will want the tale told as if it were of its own making.

Thus the pagan will be sanctified, the tragic become laughable; great lovers will stoop to sentiment, and demons dwindle to clockwork toys.

Nothing is fixed. In and out the, shuttle goes, fact and fiction, mind and matter, woven into patterns that may have only this in common: that hidden amongst them is a filigree which will with time become a world.

It must be arbitrary then, the place at which we chose to embark.

Somewhere between a past half forgotten and a future as yet only glimpsed.

This place, for instance.

(For a book I've never finished, Weaveworld has left is mark on me. Another line from the novel, one that is inscribed on a book of nursery rhymes-- "That which is imagined need never be lost"-- has gripped my own imagination for decades now.)

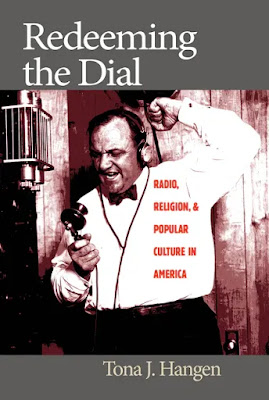

However, my favourite opening passage of any books does not come from a novel. It does not come from a classic that has been passed lovingly down the generations. It comes from a rather obscure book-- Redeeming the Dial, Radio, Religion and Popular Culture by Tona Hangen, a history of American religious radio programming between the wars. I reviewed it some years ago.

Here is the opening passage which I love so much:

Imagine a wind-scoured farmhouse and beside it a small barn, huddled together under an ashen gray Montana sky. It is 21 January, the dead of winter, so cold that a widow woman will not venture out for anything but to milk her cows-- and even then, not too early, not until long after daybreak. She is sixty-seven years old, farming alone, tending her herd with stiffening hands that have known hard times...Inside the barn, the air is a little warmer; the cows breathe by snorting clouds of vapour, which hang in the air. The woman sings and prays as she milks, listening to a radio set on a shelf amongst the pails and coils of baling wire. She sings a familiar gospel song, adding her voice to the rippling chords of a piano and a jubilant-sounding choir in sunny Long Beach, California, thousands of miles away. They cannot hear her, of course, yet she sings. Only the cows hear; the cows, and God.

I love so many things about this passage. I think I am going to have to resort to a numbered list:

1) It opens with the word "imagine", which is always a powerful word when used as an imperative. Think of the enduring appeal of John Lennon's song "Imagine".

2) It uses the phrase "the dead of winter", which is one of my favourite phrases. Along with the "dead of night" (the title of one of the best horror films ever made), I find it impossibly evocative. It helps that I like night and winter more than most people seem to like them.

3) The scene-setting in the first sentence is simple but potent. I've always disliked descriptive writing, lacking as I do a visual imagination. However, the imagery in this sentence is too simple to burden even the poorest visual imagination.

4) The passage evokes remoteness in a way that it would be hard to equal. Montana is "big sky country". I've always loved the idea of remoteness. "The middle of nowhere", "the back of beyond". What makes the heart leap at such a thought? What makes my heart leap, at any rate? Is it the sweet fact that the world is big enough to allow such places, and so many of them? But perhaps analysing the appeal of such ideas is pointless-- each explanation would require another explanation. All I can say is that the thought of a wind-scoured farm in Montana excited me far more than the thought of Time Square or Trafalgar Square, or even the Grand Canyon or the Dingle peninsula.

5) The ghostliness of the voices on the air, the songs coming from the radio on the shelf. There is something magical about radio. As the cliché goes, "the pictures are better on the radio". Radio immerses us and yet remains invisible. I'm not a seasoned radio-listener, so in a way, the magic of the medium remains fresh to me.

6) The contrast of the cold Montana barn and "sunny Long Beach, California, thousands of miles away" is delicious. How much of life's pleasure is to be found in contrasts? Masculinity and femininity, salt and vinegar, ice-cream on a hot summer's day...I especially like contrasts such as this one. I used to live beside a tanning salon called Miami Sun, which had the silhouette of palm trees on its sign, and its front was painted hot orange. It was always a charming sight in the drizzle and darkness of a November night in Dublin.

8) There is a particularly American flavour to the remoteness and rawness of this passage. The idea of the boondocks, the great open spaces, small town America, the heartlands, cornfields and apple pie and the family Bible. If you don't "get" the appeal of this, I doubt anybody can show it to you. But I'm guessing you do get it.

I'd have to agree with the many who argued that the opening paragraph of Anna Karenina is the possibly the most capturing ever; the people mentioned were actually not the main characters, but that often turns out to be the case also.

ReplyDeleteDue to the high profile of the film, I found the opening line of Give With the Wind quite striking: what did Vivien Leigh think of the novel starting with "Scarlett O'Hara was not beautiful"?

I've never read the book! Yes, I can imagine her taking exception to that!

DeleteI haven't read Anna Karenina either, to my shame.

'Time for lunch,' the opening line of Gordon Boshell's schoolboy thriller 'The Black Mercedes', I always thought was rather well-chosen, not to say appealing to the target audience.

ReplyDeleteYou do quote some remarkable opening lines here, though, and yes, I do get it. The radio at night... something about the contrast between the intimacy of the voice and its distance is profoundly poetic.

"Time for lunch" will always get my attention!

DeleteRadio is very poetic. Every now and then I wonder why I've so rarely listened to it. But I probably already have enough technology in my life!